Chapter 9 Quality management

543.

543. The product of any census of population and housing is information, and confidence in the quality of that information is critical. The management of quality must therefore play a central role within any country’s census.

544.

544. A quality management programme is an essential element in the overall census programme, regardless of whether it is a traditional, register-based or combined census, and should touch on all activities during planning, the development period, operational activities such as data collection and processing, through to evaluation and dissemination of results.

545.

545. The focus of any quality management programme is to prevent errors from occurring or reoccurring, to detect errors easily and early enough to allow taking corrective actions. Without such a programme, the census data, when finally produced, may contain errors, which might severely diminish the usefulness of the results. If data are of poor quality, then decisions based on these data can lead to costly mistakes. Eventually the credibility of the entire census may be called into question.

546.

546. Establishing a quality management programme and setting quality standards at the planning stage is crucial to the success of the overall census operation. The quality management programme should be developed as part of the overall census project and integrated with other census plans, schedules and procedures. Furthermore, it should not be seen as a stand-alone exercise, but it should be part of a broader approach to quality management across the NSO.

547.

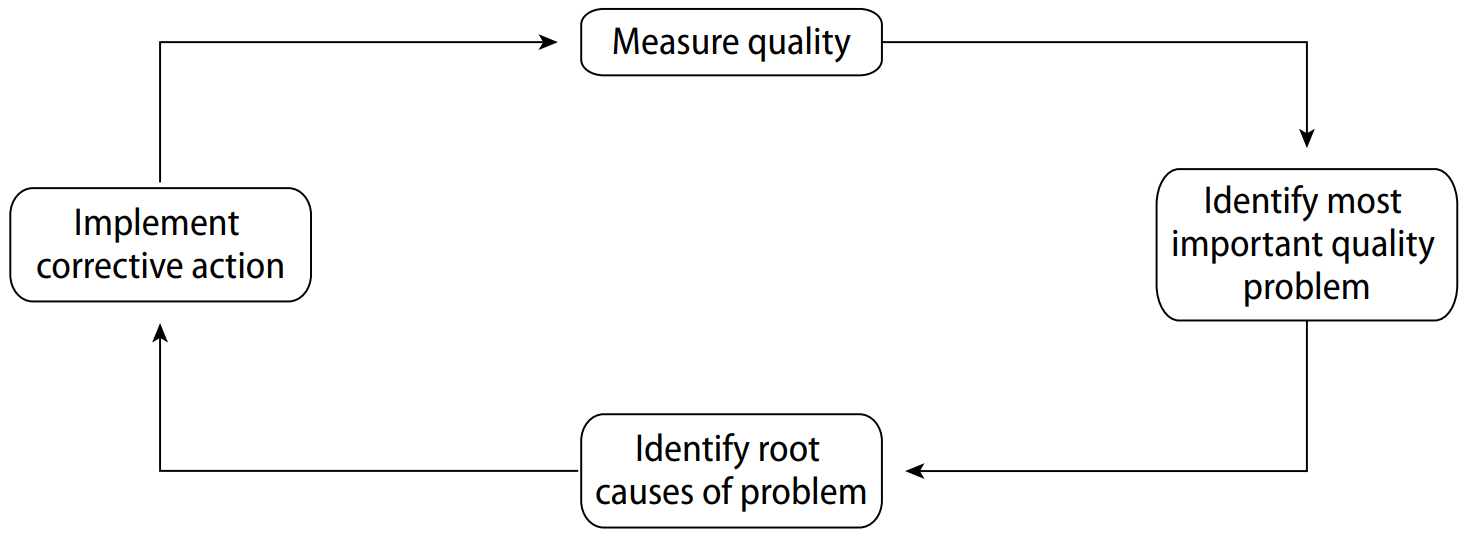

547. A major goal of any quality management programme is to systematically build in quality from the beginning through the sound application of knowledge and expertise by employees at many levels, and through defined quality assurance processes and reviews. It will also include reactive components to detect errors so that remedial actions can be taken during census operations, as represented by the well-known Quality assurance circle (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Quality assurance circle

Quality assurance circle

Source: Principles and Recommendations for Population and Housing Censuses – Revision 3, United Nations, New York, 2017.

548.

548. Lessons learnt from previous censuses and experience learnt by other NSOs are very useful to plan for a quality management programme for the current census. Therefore, a well-documented evaluation of previous experiences is of critical importance so that errors detected from previous censuses or similar activities are used as the basis for developing a quality management for the next census. Also, the integration of census activities with other NSO’s core activities should be promoted, in order to avoid the loss of institutional knowledge that might follow the end of each census activities (especially in countries where censuses are conducted are discrete projects). Firstly, this chapter defines the different dimensions of “information quality” and then describes a framework that can be used to manage quality across these dimensions through the full census lifecycle. Furthermore, it presents a paragraph devoted to quality management in register-based and combined censuses. Finally, it includes a short paragraph with some additional guidance concerning quality assurance in an outsourcing environment. Section 9.6 provides further guidance about how the framework can be applied in practice to each dimension and additional detail on the following topics: operational quality control; questionnaire design; management of coverage error; systems development; methods of census evaluation (including a case study on content evaluation); measuring record-linkage quality; measuring editing and imputation quality.

549.

549. It is generally accepted that there are six dimensions of statistical quality.46 They are described below.

9.2.1 Relevance

9.2.1 Relevance

550.

550. The relevance of statistical information reflects the degree to which it meets the needs of users. The challenge for a census programme is to balance conflicting user requirements so as to go as far as possible in satisfying the most important needs within resource constraints. This dimension of quality is particularly important in census content development and in dissemination. Related to relevance is “completeness”, defined as the degree to which statistics fully cover the phenomenon they are supposed to describe.

9.2.2 Accuracy

9.2.2 Accuracy

551.

551. The accuracy of statistical information is the degree to which the information correctly describes the phenomena it was designed to measure. It is usually characterized in terms of error in statistical estimates and is traditionally broken down into bias and variance. While bias refers to non-sampling errors, variance refers to sampling errors, therefore, in a census context, variance only applies in situations where a short form/long form strategy is used (i.e. the full questionnaire or long form is completed only for a sample of households), or where only a sample of records is processed. Sampling errors are typically measured and communicated using the Mean Squared Error (MSE) framework and/or through confidence intervals. However, such measurements do not cover non-sampling errors, which are particularly important in the context of censuses, where the aim is to the capture the full population. Accuracy can also be described in terms of major sources of error (for example coverage, sampling, non-response, response, data capture, coding).

552.

552. For statistics derived from administrative data, the key sources of error in the context of censuses are non-sampling errors, i.e. representation (coverage) and measurement errors.47

553.

553. Representation errors (errors relating to the target units) might occur if data are not reported correctly to the data supplier resulting, for example, from non-registration or delayed self-registration on an administrative register (e.g., birth, death, or full population register). Some data records may not be transmitted to the NSO because of technical problems or be transmitted with errors if administrative sources are not regularly updated by the data supplier (resulting in duplicates and/or omissions).

554.

554. Implausible or missing values are indicative of measurement errors (that is, error within variables) and may reduce the accuracy of the raw data. To assess whether a value is implausible or missing, it is important to examine not only specific records, but also variable distributions for all records. Reasons for a lack of accuracy might be technical, such as errors in the process of data transfer. Or a lack of accuracy may be systematic. For example, this may result from an inadequate submission or maintenance on the part of the data supplier, particularly if the variable is not of administrative importance for the data supplier, therefore it is not systematically recorded (e.g. a person’s occupation in the population register). Missing values may also be due to an administrative source (or variables on a source) being only recently established.

555.

555. It should be noted that representation errors may cause measurement errors where the unit of statistical measurement changes. For example, a person missing in the administrative population register may lead to an understated value for the variable “size of household”. For an overall coverage assessment of a dataset, an examination of both over- and under-coverage is needed. Under-coverage may be of particular importance with respect to “hard-to-reach” populations.

9.2.3 Timeliness

9.2.3 Timeliness

556.

556. Timeliness refers to the delay between the time reference point (usually census day) to which the information pertains and the date on which the information becomes available. Often for a census there are several release dates to be considered in a dissemination schedule. Typically, there is a trade-off against accuracy. Timeliness can also affect relevance. Related to timeliness is “punctuality”, defined as the degree to which the availability of the data meets pre-announced release dates.

9.2.4 Accessibility

9.2.4 Accessibility

557.

557. The accessibility of statistical information refers to the ease with which it can be obtained. This includes the ease with which the existence of information can be ascertained, as well as the suitability of the form or medium through which the information can be accessed. The data obtained are of great value to many users including central government, local administrations, private organizations and the public at large. To maximize the benefit of the information obtained, it should be widely accessible to all of these potential users. Consequently, censuses often provide a mix of free products, standard cost products and a user pay service for ad hoc commissioned or customized products. The strategy adopted and the cost of the services also affects accessibility. Related to accessibility is “clarity” i.e. the degree to which the data are understood (regardless of how accessible they are), particularly for non-experts, which is in turn related to interpretability (see below).

9.2.5 Interpretability

9.2.5 Interpretability

558.

558. The interpretability of statistical information reflects the availability of supplementary information and metadata necessary to interpret and use it. This information usually covers the underlying concepts, definitions, variables and classifications used, the methodology of data collection and processing, and indications of the accuracy of the information.

9.2.6 Coherence

9.2.6 Coherence

559.

559. Coherence reflects the degree to which the census information can be successfully brought together with other statistical information within a broad analytic framework and over time. Data are most useful when comparable across space, such as between countries or between regions within a country, and over time. More and more emphasis is also put on enabling comparison of geography over time, as well as maintaining consistency and comparison of census topics from one census to another. The use of standard concepts, definitions and classifications - possibly agreed at the international level - promotes coherence. Comparability can be seen as a special case of coherence, where coherence is the degree to which data that are derived from different sources or methods, but refer to the same topic, are similar, while comparability is the degree to which data can be compared across countries, regions, subpopulations and time. The degree of quality on coherence can be assessed via a programme of certification and validation of the census information as compared to corresponding information from surveys and administrative sources. Equally important is internal coherence of data, referring to the consistency of information across different topics of the census and census outputs.

560.

560. Related to both comparability and accuracy is the dimension of reliability, which can be defined as the degree of closeness of initial estimates to subsequent estimated values. Administrative data, by nature, can be subject to improvements in accuracy over time (e.g., coverage can improve, as lagged registrations and de-registrations become available, and the quality of measurements can also improve). Therefore, an NSO can make use of “new” data to improve their census statistics, revising previous estimates. However, this needs to be balanced against user needs with respect to revisions.

561.

561. Section 9.4 is devoted to quality assessment of administrative sources, with specific reference to the four quality assessment stages (Source, Data, Process and Output) identified as relevant for administrative sources.

562.

562. Quality management is generally considered to have five main components.48 They are described below.

9.3.1 Setting quality targets

9.3.1 Setting quality targets

563.

563. Setting census quality targets for each of these dimensions at the outset of the census programme enables all involved to know what they are aiming to achieve and, crucially, to determine what it will cost. Early publication of these targets also involves stakeholders, users of the data in particular, to comment and feed in their requirements. In reality, there will be iterations of such targets as initial aspirations may turn out to be unaffordable or unachievable in the time available. Having such a discussion is crucial at the outset to enable realistic, affordable targets to be set and stakeholder expectations to be managed.

564.

564. Simplistically, setting quality targets enables an NSO to answer the question “What does good look like?” and enables a dialogue with stakeholders about “How good is good enough?”.

565.

565. It is easier to set targets for some dimensions than others. It is relatively straightforward to set targets for accuracy, timeliness and accessibility. For example, simple targets could be of the form:

(a) Accuracy: “We will aim to produce national population estimates that are within X per cent of the (unknown) true value with 95 per cent confidence.”49;

(b) Timeliness: “We will aim to publish our first population estimates within one year of census day”;

(c) Accessibility: “We will aim to disseminate all outputs online.”50

566.

566. Setting targets for some of the other dimensions, however, is not so straightforward, and it is sometime helpful to consider setting process-related, rather than outcome-related, targets. For example:

(a) Relevance: “We will consult with users on the required census content at least two years before finalizing the content of the census questionnaire”.

567.

567. It is clear that even such simplistic targets will have a significant impact on cost and timetable, hence the necessity of considering such aims early in the planning process. It is suggested, therefore, that all NSOs should set targets for each dimension of quality at the early stages in the census programmes, and that these should be published to enable stakeholder views to be taken into account. It is particularly important to set targets for accuracy.

9.3.2 Quality design

9.3.2 Quality design

568.

568. Having set quality targets, it is necessary to consider whether or not the census statistical and operation design is capable of meeting those targets. This can draw on experience of previous censuses or wider international experience.

569.

569. Pre-census tests (or pilots) provide a useful vehicle for planning and developing the actual census. Census tests can be conducted as a national sample (useful for testing content, mail and/or Internet response, and other questionnaire-related features of the census), or as a site test (useful for testing operational procedures). Other pre-census testing could involve cognitive testing of the questionnaire, research and testing of the automated processes for address list development, questionnaire addressing and mail out, messaging (styles of initial contact letters and reminders and content of mail materials) and the mail contact strategy, data collection, data capture, data processing, communication approaches, conducting research into the use of administrative records, improved cost modelling and improved methods of coverage measurement.

570.

570. Prior to conducting the actual census, a complete rehearsal provides an opportunity to test the full array of operations, procedures and questions, much like a play’s dress rehearsal provides an opportunity to “address any remaining issues” before the actual event.

571.

571. Such testing should result in a review of the initial quality targets to confirm their achievability. It may at this point be necessary to change budgets, timetables, or the targets themselves if testing has shown them to be unachievable. Rehearsals should, therefore, be undertaken late enough in the planning stage to be able to assess the final census design yet earlier enough to enable any necessary changes to be implemented.

9.3.3 Operational quality control

9.3.3 Operational quality control

572.

572. Because of the size and complexity of census operations, it is likely that errors of one kind or another may arise at any stage. These errors can easily lead to serious coverage or content errors, cost overruns or major delays in completing the census. If not anticipated and controlled during implementation they can introduce non-sampling error to the point of rendering results useless.

573.

573. To minimize this risk, it is essential to monitor and control errors at all stages of census operations, including pre-enumeration, enumeration, document flow, coding, data capture, editing, tabulation and data dissemination. Every national census organization should establish a system of operational quality control.

574.

574. The dimensions of quality outlined above are overlapping and interrelated and each must be adequately managed if information is to be fit for use. Each phase in executing a census may require emphasis on different elements of quality. Again, this requires careful design at the outset to identify:

(a) The types of errors that may occur at each phase of the operation;

(b) What information is required to enable such errors to be identified, should they occur;

(c) How this information will be collected in a timely fashion during live operations; and

(d) What actions will be taken should the error be found to have occurred (ideally before the phase is complete).

575.

575. Quality control requires careful planning and testing. Operational quality control processes and systems should be included in both pre-census tests as well as rehearsals to ensure they work as expected during census operations.

576.

576. There is no single standard operational quality control system that can be applied to all censuses or even to all steps within a census. Census designers and administrators must keep in mind that no matter how much effort is expended, complete coverage and accuracy in the census data are unattainable goals. However, clear quality targets should sit at the heart of decision-making processes and efforts to first detect and then to control errors should be at a level that is sufficient to produce data of a reasonable quality within the constraints of the budget and time allotted.

577.

577. The development of a Risk Management plan identifying potential risks and strategies for dealing with them is also crucial to ensure a sound operational quality control system. The Risk Management Plan should identify potential risk events and their probability of occurring, provide measures of potential impact, offer strategies for dealing with risks if they occur, and identify the area(s) responsible for addressing each risk event. The Plan should be a dynamic document where risks can be modified as needed (see Chapter 11).

9.3.4 Quality assurance and improvement

9.3.4 Quality assurance and improvement

578.

578. Once data collection and processing operations are complete, it is essential that final statistics are quality assured and, where possible, improvement made to the results prior to publication if significant problems are discovered.

579.

579. Quality assurance can be through comparison with statistics from other surveys, through comparison with statistics from administrative data sources, or through analysis of information collected as part of operational quality control. But such quality assurance is challenging, and sufficient time should be allowed from the outset to enable such studies to be completed prior to publication.

9.3.5 Quality evaluation and reporting

9.3.5 Quality evaluation and reporting

580.

580. It is generally recognized that a population census is never perfect and that, despite rigorous quality control and quality assurance, errors can, and do, occur. Most errors in the census results are classified into two major categories: coverage errors and content errors. Coverage errors are those that arise due to omissions or duplications of persons or housing units in the census enumeration. Content errors are errors that arise in the incorrect reporting or recording (or linking) of the characteristics of persons, households and housing units enumerated in the census. A third type of error classified as operational error can occur during field data collection or during data processing.

581.

581. Many countries recognize the need to evaluate the overall quality of their census results and employ various methods for evaluating census coverage as well as certain types of content error. In fact, some countries, the United Kingdom for example,51 includes coverage assessment as an integral part of the census process and aims to publish all results after an adjustment for coverage error. Most countries, however, undertake coverage assessment only as part of their evaluation process, as described in section 9.6.14.1.

582.

582. A comprehensive evaluation programme should, however, also include assessments of the success of census operations, in each of its phases. Countries should ensure, therefore, that their overall census evaluation effort addresses the census process (hereafter referred to as operational assessments), as well as the results (referred to as evaluations). Together, operational assessments and evaluations tell us “How well we did”. A third component of a comprehensive research includes experiments. Experiments tell us “How can we do better?” Thus:

(a) Operational assessments document: final volumes, rates and costs for individual operations or processes, using data from production files and activities; quality assurance files and activities; and information collected from debriefings and lessons learned. Operational assessments can include some discussion of the data, but do not involve explanation of error. The final volumes, rates and costs can be broken out by demographic, geographic level, and housing unit and/or person-level data at intermediate stages of operations or processes. Operational assessments may also document operational errors, although they will not necessarily include an explanation of how those errors affect the data. For administrative sources used in the census, operational assessment documents should include: quality assurance files and activities related to the processing of the different administrative sources, including actions taken to improve the fitness-for-use of the admin sources;

(b) Evaluations analyse, interpret and synthesize the effectiveness of census components and their impact on data quality and coverage using data collected from census operations, processes, systems and auxiliary data collections. For register-based and combined censuses, evaluations should also include measures such as the rates of record linking and imputation, the use of methods such as the signs-of-life and their impact on census coverage. In addition, evaluations should also be made on the impact on census output, especially for countries transitioning to admin-based census;

(c) Experiments are quantitative or qualitative studies that must occur during a census to have meaningful results to inform planning of future censuses. The census provides the best possible conditions to learn about the value of new or different methodologies or technologies and typically involve national surveys with multiple panels.52

583.

583. Evaluation efforts that focus on census results should generally be designed to serve one or more of the following main objectives:

(a) To provide users with some measures of the quality of census data to help them interpret the results;

(b) To identify as far as is practical the types and sources of error to assist the planning of future censuses; and/or

(c) Feed into the quality assurance and improvement processes and serve as a basis for constructing a best estimate of census aggregates, such as the total population, or to provide census results adjusted to take into account identified errors.53

584.

584. Evaluations of the completeness and accuracy of the data should be made by all countries, and should be issued with the initial census results to the fullest extent possible, including the detail of the methods used. In order to ensure transparency about data quality and enhance users’ confidence in the census results, it is important to assess quality of census data as much as possible prior to their release, and to make this information publicly available, even though, in order to provide detailed coverage results and information on how accurately the census counted certain population groups, it might be necessary to wait for the results of the Post-Enumeration Survey (PES) or other coverage surveys (see section 9.6.14.1). Additional results can be issued after the initial results are published. However, the evaluations of the completeness and accuracy of census data should also be included in the evaluation or quality report.

585.

585. If census estimates are adjusted in the light of quality assurance and evaluation activities (including adjustments to population counts), countries are encouraged to thoroughly document the type of changes (whether at the microdata or aggregated level) and their extent. Furthermore, countries are encouraged to document and publish the methodologies used for imputation of total non-response, detailing the techniques and rationale. They should also report the magnitude of these imputations.

586.

586. More broadly, an assessment of all six dimensions of quality should ideally be made against the initial targets set, with the results published. Such evaluations and measurements can be valuable to indicate priorities and establish quality targets standards for the next census, thus completing the quality cycle.

587.

587. A number of methods exist for carrying out census evaluations and, in practice, many countries use a combination of such methods to fully serve these objectives. A short guidance on methods of census evaluation is provided in section 9.3.5.

588.

588. Finally, census quality reports should also describe any Statistical Disclosure Control method used to ensure data confidentiality and the resulting consequences on data quality (such as the level of loss of accuracy).

589.

589. Indeed, ensuring data confidentiality is an indispensable element for maintaining the trust of respondents and the integrity of the NSO. If respondents believe or perceive that a national statistical office does not protect the confidentiality of their data, they will be less likely to cooperate or provide accurate information in future censuses. This may in turn affect the accuracy and relevance of the resulting statistics.

590.

590. Therefore, NSOs should aim to determine optimal Statistical Disclosure Control (SDC methods and solutions that minimize disclosure risk while keeping information loss to a minimum. Users of census data should be aware of the logic and the broad methodology behind statistical disclosure control methods applied to data, and their impact on census data, especially at lower geographies (such as at the squared kilometre grid level).

591.

591. Administrative sources may be used to enhance or to supplement a field enumeration-based census, to conduct a combined census, or in the construction of a fully register-based census. In the last census round there has been a clear trend towards increased use of administrative data in censuses across the countries of UNECE region and beyond, in line with a more generalized trend towards increased use of administrative data for statistical production, further increased and/or accelerated as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly to support the production of census statistics where field data collection has not been possible or has been delayed.54

592.

592. Additional dimensions are usually considered (e.g. the institutional environment, linkability, accuracy of record linkage, accuracy of conflict resolution) when assessing quality of administrative sources for use in censuses. Indeed, even though the six standard quality dimensions (see section 9.2) capture many relevant aspects of administrative data quality, alone they are considered not always sufficient to assess the quality of administrative data (Daas et al, 2008, p. 2).55

593.

593. Many quality considerations must be taken into account before incorporating the use of administrative sources into a census. It is important that NSOs understand the strengths and limitations of administrative data in order to make the right decisions about the use of such data56. The pandemic has also had a significant impact on the quality and content of administrative sources.57

594.

594. In a census context, the quality of administrative data used should be considered in relation to the ways data are collected and processed by data suppliers and NSOs, through to the final census outputs. Throughout the process, errors may occur which will compromise quality. Assessing the quality of administrative sources requires mapping the errors which may occur before and after the data is supplied to NSOs and determining how any such errors can be mitigated (e.g. through changes to collection, processing and/or integration with other sources).

595.

595. Quality measurement and assurance should be undertaken throughout all stages of the framework. More precisely, four stages of production have been identified in relation to the use of administrative sources in censuses, applicable regardless of census type (i.e. regardless of the census process in which administrative sources are being used), broadly related to the lifecycle of using administrative data in the census:

(a) Source stage: understanding, evaluating and working to acquire a source;

(b) Data stage: receiving the actual data and assessing its quality;

(c) Process stage: processing the administrative data for use in the census;

(d) Output stage: assessing the quality of the census outputs that use administrative data.58

596.

596. The quality of administrative data may be assessed, by identifying the key quality dimensions at each stage and the respective tools and indicators for quality assessment. Besides the six standard quality dimensions, additional dimensions are taken into account.

597.

597. In the Source stage (a), information is gathered about an administrative source through communication with the data supplier and by reviewing existing metadata. At this Stage, the focus is on assessing the relevance of the source against the needs of the census, considering the dimensions of accuracy, timeliness, coherence and comparability, accessibility and interpretability. An assessment is also made about the institutional environment, including whether or not the data supplier can meet the needs of the NSO, considering factors such as the strength of the relationship with the supplier and the status of the supplier.

598.

598. In the Data stage (b) of the assessment, data are received from the data supplier and are assessed through analysis and comparisons with other data sources. Besides standard quality dimensions, other dimensions such as validation and harmonization arrangements put in place upon data transfer to NSO and linkability (defined as availability of adequate linkage variables) are involved at this stage.

599.

599. During both the Source and Data stages, the assessment and measurement of quality is set against many data quality dimensions, using various tools and indicators, e.g. comparisons with alternative sources will reveal measurement or representation errors, to be measured against set accuracy targets. The information and insight gained through the Source and Data Stages are useful not only to determine whether a particular source could be used in the census, but also to determine the necessary processing of the administrative data for use in a census.

600.

600. In the Process stage (c), administrative data are transformed using the information gained at the Source and Data Stages.59 The processes commonly carried out on administrative sources for census use are: record linkage; assessment of coverage errors (e.g. by using the “signs of life” methodology), resolving inconsistencies from different sources, editing and imputation. The quality of administrative data at this stage is to be assessed against several dimensions including accuracy of record linkage (where multiple sources are linked), accuracy of conflict resolution (referred to the methods for deciding between sources where different sources are linked and the same attributes are available in them), accuracy of editing and imputation (where census variables or units are derived or constructed through imputation or modelling techniques).

601.

601. Finally, in the Output stage (d), the quality assessment of census outputs which use administrative data is carried out. Conceptually, this is no different from the assessment of the outputs of a questionnaire-based census, while at the same time it will provide valuable information about where there may be limitations or concerns about the administrative data, or the processing of these data, which were not identified initially at the Source, Data and Process Stages. There is an iterative process of assessment, which can inform both ongoing improvements to the administrative sources (working with the data supplier to improve the source) and improvements to the processing of the administrative data by the NSO.

602.

602. Some countries may wish to outsource certain parts of census operations. The motivations and considerations for outsourcing have already been discussed more fully in section 4.4. In the context of quality management, the outsourcing of components of census operations still requires the census agency to take full responsibility for, and manage the quality of, the census data. This aspect should never be delegated.

603.

603. In setting up outsourcing arrangements, the census agency needs to ensure that it continues to have the ability to both understand and manipulate those elements that contribute to final data quality.

604.

604. Some approaches to outsourcing put an emphasis on “turnkey” arrangements, in which contractors deliver systems according to a set of predetermined client specifications with the expectation that the client focuses solely on the outputs and not the internal workings of the system. This assumes that the census agency completely understands and can fully anticipate all data quality issues that might arise during the census and has included these in the specifications. The client is not expected to have any understanding of how these systems work or how they might contribute to the final outputs. Any changes to the system typically require cumbersome processes to determine contract responsibilities and heavy financial costs. This sort of approach effectively hands over the quality of the census data to the contractor, while the risks associated with intervention remain with the census agency. It removes any flexibility and greatly restricts the ability of the census agency to react to quality problems that emerge during processing. This “turnkey” approach is not recommended.

605.

605. Suppliers should be made fully aware of the quality targets set at the outset of the census programme, and the quality requirements of the outsourced components that enable the overall census quality targets to be achieved. Operational quality control should apply to outsourced services in the same way as those that are carried out internally.

606.

606. Even when components are outsourced, census agency staff should have an understanding of how such systems work, for example, automatic text recognition engines and coding algorithms, and have the ability to change the tolerances or parameters of these systems at little cost and in a timely manner during processing. Varying these parameters will allow the census agency to determine and manage the appropriate balance between data quality, cost and timeliness as processing progresses.

9.6.1 Introduction

9.6.1 Introduction

607.

607. Quality must be managed in an integrated fashion within the broader context of undertaking the entire census programme. Census management will require input and support from all functional areas, and it is within this context that trade-offs necessary to ensure an appropriate balance between quality and concerns of cost, response burden and other factors will be made. There needs to be adequate staff with people able to speak with expertise and authority while being sensitive to the need to weigh competing pressures regarding dimensions of quality and other factors to reach a consensus. Those responsible for each aspect of census work must be equipped with appropriate expertise. Each of them will need to develop and implement strategies addressing many aspects of quality. In doing so they must be sensitive not only to their own quality requirements but also to their interactions with quality requirements of others. Strategies to facilitate the necessary information sharing and joint consideration of cross-cutting quality issues are vital.

608.

608. Quality requirements need to receive appropriate attention during design, implementation and assessment. Subject matter experts will bring knowledge of content, client needs, relevance and coherence. Statistical methodologists bring their expertise on statistical methods and data quality trade-offs, especially with respect to accuracy, timeliness and cost. Operations experts bring experience in operational methods, and concerns for practicality, efficiency, field staff, respondents and operational quality control. The systems experts bring knowledge of technology standards and tools that will help facilitate achievement of quality, particularly in the timeliness and accuracy dimensions. In collaboration with subject matter experts, dissemination experts will bring a focus to accessibility and interpretability.

609.

609. This section provides further guidance about implementing a quality management programme. Firstly, the six dimensions of quality are taken in turn, with a description of how the five components of the quality management framework might apply to each. Later sections then provide further detail on:

(a) Operational quality control;

(b) Questionnaire design;

(c) Management of coverage error;

(d) Systems development;

(e) Census evaluation;

(f) Measuring record linkage quality; and

(g) Measuring editing and imputation quality in register-based censuses.

610.

610. As a reminder, the six dimensions of quality are:

(a) Relevance;

(b) Accuracy;

(c) Timeliness;

(d) Accessibility;

(e) Interpretability; and

(f) Coherence.

611.

611. and the five components of the quality management framework are:

(a) Setting quality targets;

(b) Quality design;

(c) Operational quality control;

(d) Quality assurance and improvement; and

(e) Quality evaluation and reporting.

9.6.2 Managing relevance

9.6.2 Managing relevance

612.

612. The programmes and outputs of a National Statistical Office (NSO) must reflect the country’s most important information needs. Relevance for the census must therefore be managed within this broader context. At the stage of setting quality targets it is necessary to discuss how much change in the questionnaire (or the information to be taken from registers) will be contemplated. In cases of severe budget restrictions, some countries have agreed to a policy of minimal change or no change to minimize testing requirements and quality risks. Clearly, this impacts the relevance of the final statistics, but having such discussions at the outset, with stakeholders, is essential.

613.

613. At the stage of quality design, relevance is managed through processes to assess the relevance of previous census content and to identify new or emerging information gaps that may be appropriately filled via the census. Major processes to achieve this can be described as client and stakeholder feedback mechanisms and programme review and data analysis. Information from these processes can then be used to ensure the relevance of census content and outputs.

614.

614. Important feedback mechanisms might include: consultations with key government departments and agencies; advice from professional advisory committees in major subject matter areas; user feedback and market research; ad hoc consultations with interested groups; and liaison with statistical offices from other countries.

615.

615. While the primary purpose of data analysis is to advance understanding of phenomena, it also provides feedback on the adequacy and completeness of the data used in the analysis. By identifying questions that the census data cannot answer it can pinpoint gaps and weaknesses. This must be taken in the context of the analytic potential of other data holdings of the NSO. There is a reduced focus on relevance during Operational quality control and Quality assurance and improvement, but the emphasis increases again for Quality evaluation and reporting, when the published outputs can be reviewed to consider how well they met the originally stated information needs.

9.6.3 Managing accuracy

9.6.3 Managing accuracy

616.

616. Management of accuracy requires attention during all five steps in the quality management framework. Firstly, when setting quality targets, accuracy targets should be set as these will fundamentally affect the census costs and design.

617.

617. During quality design, parameters and decisions will have a direct impact on accuracy. This includes the design of later components of the quality management framework. The accuracy achieved will depend on the explicit methods put in place for operational quality control and quality assurance and improvement. If these processes are not built in from the outset, including the required data collection processes and feedback loops, it will be much more challenging for them to be implemented effectively.

618.

618. A number of key aspects of design should be considered in every census to ensure that accuracy concerns are given appropriate attention:

(a) Explicit consideration of overall trade-offs between accuracy, cost, timeliness and respondent burden during the design phase;

(b) Adequate justification for each question asked and appropriate pre-testing of questions and questionnaires in each mode of collection, while also ensuring that the set of questions is sufficient to meet requirements;

(c) Assessment of the coverage of the target population. This relates to the adequacy of the geographic infrastructure upon which collection and dissemination geography will be based. It may also relate to the adequacy of address lists to be used in areas where mail out of census questionnaires takes place;

(d) Proper consideration of sampling and estimation options. For example, sampling could be used at the collection stage through the use of short and long form questionnaires in order to reduce respondent burden and collection costs. Alternatively, sampling could be introduced after collection, by processing only a sample of records, at least for a subset of characteristics, in order to produce more timely results or to control processing costs. In either case, careful consideration should be given to the size and design of the sample and to the weighting and other estimation procedures needed;

(e) Adequate measures in place for facilitating and encouraging accurate response, following up non-response and dealing with missing data;

(f) Proper consideration of the need for operational quality control;

(g) Appropriate quality assurance for the final statistics.

619.

619. While individual programme managers may have considerable flexibility in implementing specific practices and methods, this should be done in an integrated fashion within the overall management of census quality.

620.

620. A good design will always contain protection against implementation errors through, for example: adequate selection and training of staff; suitable supervisory structures; carefully written and tested procedures and systems; and operational quality control procedures.

621.

621. Mechanisms for operational quality control should be built into all processes as part of the design. Information is needed to monitor and correct problems arising during implementation. This requires a timely information system that provides managers with the information they need to adjust or correct problems while work is in progress. There is an overlap here with quality assurance and improvement and quality evaluation and reporting as much of the information collected during operational quality control is also needed to assess whether the design was carried out as planned, and to identify problem areas and lessons learned from operations in order to aid design for future censuses.

622.

622. Some examples of activities that could be undertaken to manage and monitor accuracy during implementation and operations are:

(a) Regular reporting and analysis of response rates and completion rates during collection;

(b) Monitoring non-response follow-up rates;

(c) Monitoring interviewer feedback;

(d) Monitoring coverage checks and controls;

(e) Monitoring of edit failure rates and the progress of corrective actions;

(f) Monitoring of results of quality control procedures during collection and processing;

(g) Monitoring of expenditures against progress; and

(h) Development, implementation and monitoring of contingency plans.

623.

623. Where applicable, the activities outlined in paragraph 622 above should be at different geographic levels or aggregations that are useful for each level of management, including those suitable for supervising and correcting the actions of groups or individuals involved.

624.

624. Accuracy is multidimensional. Indicators may touch on many aspects of census collection, processing and estimation. Primary areas of assessment include the following:

(a) Assessment of coverage error, both under-coverage and over-coverage. In most countries this is done via a post-enumeration coverage survey and using dual system estimation methods.60 Comparisons with official population estimates, typically projections from the previous census, are often also used as an assessment tool;

(b) Non-response rates and imputation rates (including imputation rate of total non-response);

(c) Data capture error rates, coding error rates;

(d) For register-based/combined censuses, linkage error rates (i.e. errors in the record linkage process: e.g. false positives/negatives);

(e) For register-based/combined censuses, editing rate i.e. the number of corrections needed to resolve inconsistencies between sources at micro-data level;

(f) Measures of sampling error, where applicable; and

(g) Any other serious accuracy or consistency problems with the results. This relates closely to coherence and allows for the possibility that problems were experienced with a particular aspect of the census resulting in a need for caution in using results.

9.6.4 Managing timeliness

9.6.4 Managing timeliness

625.

625. Planned timeliness is a decision to be made when setting quality standards, refined, if necessary, during quality design, if resources or practicalities indicate that the ideal timeframes are not achievable. There are often important trade-offs to be made with accuracy and relevance. More timely information may be more relevant but less accurate. So, although timeliness is important it is not an unconditional objective. Many of the factors described under accuracy apply equally here. Timeliness is also directly affected by fundamental time requirements to collect and process census data giving an adequate allowance for operational quality control and quality assurance and improvement. It might be tempting to aim for challenging timeframes for outputs at the early stages in census preparations, but these should be tempered by the experience gained from any quality evaluation of previous census operations.

626.

626. Major information releases should have publication dates announced well in advance. This helps users plan and provides internal discipline in working within set time frames.

627.

627. For customized/commissioned information retrieval services, the appropriate timeliness measure is the elapsed time between the receipt of a clear request and the delivery of the information product to the client. Service standards should be in place for such services and announced beforehand.

9.6.5 Managing accessibility

9.6.5 Managing accessibility

628.

628. Census information must be readily accessible to users. Statistical information that users are unaware of, cannot locate, are unable to access, or cannot afford to purchase is of no value to them. In most statistical offices, corporate-wide dissemination policies and delivery systems will determine most aspects of accessibility. Decisions about output dissemination methods and policies are often made late in the census process, as the focus is often on the challenges of data collection and processing. This can lead to later time and resource pressures, to the detriment of accessibility. Explicitly setting aims and polices when setting quality targets for the other dimensions of quality can help reduce this impact, as it enables costs and development timescales to be better estimated during quality design.

629.

629. In determining information product definition and design, managers should take careful account of client demands. Market research and client liaison will help determine these. The proposed aims and output designs, having been defined, can then be discussed with users, with appropriate modifications, in a controlled way. Whilst not strictly operational quality control or quality assurance and improvement, there are nonetheless parallels to these components in such discussions.

630.

630. In today’s world the Internet is the primary dissemination vehicle. It should include not only the data released but also information about the data (metadata) such as data quality statements and descriptions of the concepts, definitions and methods used. Use should also be made of appropriate links to the NSO’s corporate dissemination vehicles.

631.

631. Finally, as part of quality evaluation, client feedback should be monitored on the content of the output products and on the mode of dissemination with a view to future improvements.

632.

632. The information needs of the analytic community present some particular requirements. Analysts often need access to microdata records to facilitate specific analyses. This presents special challenges in order to continue to respect the requirements for the maintenance of the confidentiality of census data. A number of means could be used to address these needs. Public use microdata files, typically a sample of census records that have been pre-screened to protect confidentiality can be valuable for analysts. Custom retrieval services where specific analyses, designed by external analysts, can be conducted by staff of the statistical office may meet the needs of some analysts.

9.6.6 Managing interpretability

9.6.6 Managing interpretability

633.

633. Managing interpretability is primarily concerned with providing metadata. Information needed by users to understand census information falls under three broad headings: the concepts, definitions and classifications that underlie the data; the methods used to collect and process the data; and measures of data quality. The first of these also relates to coherence.

634.

634. A further aid to users is the interpretation of census information as it is released. Commentary on the primary messages that the data contains can assist users in initial understanding of the information. As with accessibility, interpretability can be addressed in all five components of the quality management framework.

635.

635. As for register-based/combined censuses, the complexity of administrative data may impact the accessibility and clarity output quality dimension from a data user’s perspective. That is, users of the census data may find it difficult to understand the impact on the quality of the census outputs derived from factors such as the use of different concepts, definitions, reference dates, or the fact of being subject to lags in the updating of information and, more generally, from the fact that administrative data have not been collected for statistical purposes. Countries are encouraged to provide users with the relevant information on the use of administrative data and on the impact this may have on the quality of census outputs, especially when transitioning from a field-based to a register-based census.

9.6.7 Managing coherence

9.6.7 Managing coherence

636.

636. Coherence is multidimensional. Objectives for coherence of census data include:

(a) Coherence of census data within itself;

(b) Coherence with data and information from prior censuses;

(c) Coherence with other statistical information available from the statistical office on the same or related phenomena; and

(d) Coherence with information from censuses of other countries.

637.

637. Aims for coherence should be set when setting quality standards as these will drive decisions during quality design. For example, there will be trade-offs to be made about the degree with which to standardise across programmes within NSOs and, for international standards, between countries. Subsequent decisions during quality design will need to be made about the development and use of standard frameworks, concepts, variables, classifications and nomenclature for all subject matters that are measured.

638.

638. The census must ensure that the process of measurement does not introduce inconsistency between its data and that from other sources. Managers of other statistical programmes are, of course, equally responsible for this aspect of coherence.

639.

639. There is usually less of an emphasis on coherence during operational quality control, but the emphasis increases again during quality assurance and improvement when the emerging census results can be compared with other available sources (whether published statistics or administrative data, for example). This can highlight differences in interpretation of definitions between statistical outputs, or, indeed, errors in either the census or other surveys. Although this is more correctly concerned with managing accuracy, there is an overlap with managing coherence when issues of definition and their interpretation arise.

640.

640. After publication of census results, analysis of those data that focuses on the comparison and integration of information between the census and other sources will give insights to inform quality evaluation and reporting and the degree to which quality has been achieved in coherence. The census data should be analysed for domains and aggregations, both large and small that are considered important. Such analysis should consider totals, distributions, relations between variables or sets of variables, relations between domains, growth rates, as appropriate. Comparisons should be made to data from prior censuses and to comparable survey data.

641.

641. While other surveys or other sources of data covering census topics certainly offer views on the quality of the census, there are limitations to the information they provide and the comparisons that can be made according to the sources. Therefore, data users should be guided in exercising caution in how they interpret differences.

642.

642. NSOs should explain which population comparisons are possible, and provide guidance on how to interpret differences between demographic benchmarks and census results. E.g. results from the Labour Force Survey data are generally used for making comparisons about the population labour market (economic activity) status. In this case, users should be helped in interpreting differences due to data collection and questions design.

643.

643. As for register-based/combined censuses, the administrative sources may be subject to changes over time and inconsistencies in the way the data are collected across segments of the population. It might also happen that a new data source (an administrative register or any other source) is chosen for a particular census variable (e.g. in The Netherlands the educational attainment register (integrated source from several registers) has replaced the Labour Force Survey as a source for educational attainment. The impact of these changes on census results should be carefully evaluated and explained to census users.

9.6.8 Operational quality control

9.6.8 Operational quality control  9.6.8.1 Census activities requiring operational quality control

9.6.8.1 Census activities requiring operational quality control

644.

644. A number of census processes involve massive operations, either manual or automated. Examples of such operations include dwelling listing operations, preparation of maps, printing of census materials, enumeration procedures, data capture and editing and coding (both manual and automated). Specific operational quality control procedures are particularly relevant and important for each of these.

645.

645. Dwelling listing operations are commonly conducted by enumerators prior to delivery, or as questionnaires are dropped off at dwellings. It is particularly important at this stage to minimize both under-coverage and over-coverage of dwellings. To that end, enumerators’ procedures should include quality checks to ensure the quality of their work. As well, supervisors should have planned spot checks as listing work starts, and planned quality control procedures should be applied as work is completed.

646.

646. When census questionnaires are delivered, it is usually done on the basis of a list of addresses extracted from an address register. Address register maintenance itself will involve several steps of quality management. Nonetheless, prior to its use, the address list should be validated to confirm that each dwelling exists and is included with correct address and geo-coding information, and that no non-dwellings are included. Allowance should be made for dwellings under construction that may be completed prior to the census. If not done via administrative sources, including the use of postal code information and addresses, this validation requires a large operation in the field and is subject to errors. Since this work must be parcelled out to individual enumerators in batches, acceptance sampling quality control procedures will be appropriate. Again, spot-checking and close communications with supervisors will be important quality assurance steps.

647.

647. Enumeration, whether by interviewing or by collecting completed questionnaires from the dwellings on the list, is similar. Usually one enumerator is responsible for all work in an enumeration area and will be required to implement a number of quality checks on their own work. Further acceptance sampling procedures, implemented by supervisors, will ensure the quality of various aspects of the enumerators’ work.

648.

648. Data processing is one of the crucial steps by which raw census data are converted into a complete edited and coded master file useable for tabulations. In some of these processes the data are being transformed (for example data capture, coding) while in others the data are being corrected (for example edit and imputation). New errors can occur in any of these operations.

649.

649. Countries may find it useful to use applications to provide tools that help ensure data quality, such as:

(a) A collection application that can provide consistency and completeness checks, automatic skips and alert messages, and GPS (Global Positioning System) coordinates of the household dwelling to check the enumerator's presence;

(b) A control application for the enumeration supervisor that provides the results above as well as other summary information about each enumerator’s cases, including information that signals outliers or other unexpected results;

(c) A data transfer application at central level, with all the necessary security features (data encryption, data bandwidth fluidity) to avoid data loss in the field;

(d) A web application/dashboard for monitoring data quality via real-time indicators for management teams in the field and at central level.

9.6.8.2 Operational quality control methods

9.6.8.2 Operational quality control methods

650.

650. Clearly a census operational quality control regime comprises a wide variety of mechanisms and processes acting at various levels throughout the census programme. An important technique applicable in many census operations is statistical quality control. It primarily addresses accuracy, although depending on the operation it may also address other elements of quality. What follows is some brief basic information on quality control. For a complete explanation of these methods, the reader should refer to a standard text or reference such as Duncan (1986), Hald (1981) or Schilling (2017).61

651.

651. The success of any operational quality control programme depends on laying down quality standards or requirements; determining appropriate verification techniques; measuring quality; and providing for timely feedback from the results of the programme so that effective corrective action may be taken.

652.

652. Sample verification, complete (or 100 per cent) verification, or spot checks are the usual quality control techniques adopted in censuses.

653.

653. Verification can be dependent or independent. In dependent verification, a verifier assesses the work of a census worker by examining that work. However, the verifier may be influenced by the results obtained in the initial operation. In independent verification a job is verified independently by a verifier without reference to the original work. The original results and those of the verifier are compared; if the results agree then the work is considered correct; if not, a third, often expert, verifier may resolve the difference.

654.

654. For each operation, the quality control programme should determine which approach is appropriate and will achieve the goals of the programme while also staying within the budget.62

9.6.9 Questionnaire design

9.6.9 Questionnaire design

655.

655. The design of the census questionnaire(s) takes into account the statistical requirements of the data users, administrative requirements of the census, the requirements for data processing, as well as the characteristics of the population. Because censuses often involve multiple collection methods, testing must be performed to ensure that questionnaires will work properly for all applicable methods. The questionnaire should include elements aimed at ensuring accurate coverage of the population (for example who to include, who not to include, where to be enumerated). Qualitative testing is required to check these issues and should cover an adequate variety of situations encountered in the population. In terms of content, quality management approaches for a census are similar to those for a sample-based survey. Qualitative tests and cognitive interviews should be planned to ensure that questions are clear and properly understood not only by the general population but also by any special groups to whom certain questions are targeted or for whom there are particular issues of concern (for example, the elderly, persons living alone, or those with language difficulties).

656.

656. Web-based questionnaires can provide options not available to their printed counterparts. These options can ensure greater quality in terms of question response and coverage. Checks on such serve as opportunities for detecting inconsistencies and presenting them to respondents for correction or confirmation.

657.

657. The design of electronic questionnaires for data collection via CAPI, CAWI and CATI methods require additional considerations to make the data entry process intuitive for the enumerator or respondent. Some essential functional features that should be used in the design of the electronic questionnaires include:

(a) Questionnaire navigation should allow enumerators/respondents to move relatively freely through the questionnaire in order to enter responses in the most effective way, giving the ability to pause and resume at the last answered question with a “save and continue later” functionality. On the other hand, the design should impose some restrictions on navigation, for example, by preventing enumerators/respondents from entering certain questions without having first obtained responses from other, earlier, questions;

(b) Skipping/automated routing is one of the most important error reducing features in electronic questionnaires. It obviates responding to questions that should be skipped. It also avoids the converse – skipping questions that should be asked, thus minimizing the need to impute for missing responses. Basic skips allow the response to a particular question to determine whether or not the next question is relevant, while complex skips are those that either use responses from several previous questions to determine whether the next question is relevant;

(c) Pre-coding allows relevant questions to be answered from pre-coded drop-down menus. In some cases, drop-down menus could be altered dynamically, depending on previous responses, so that the interviewer is never presented with an impossible response code;

(d) Validation: Real-time data validation checks can correct inadmissible or inconsistent responses that could be the result of either interviewer or respondent error, thus reducing the amount of post-enumeration data edits.

658.

658. The testing programme should ensure that these features are thoroughly tested prior to questionnaire finalization.

659.

659. All of these factors should be tested on a small scale (qualitative testing) and then on a large one with a significant number of respondents. A large-scale test can detect a variety of potential issues that qualitative testing cannot. Such tests also make it possible to compare different design and format possibilities via split sample designs. The large-scale test also facilitates assessing how well the questionnaire fits into other census operations (for example collection, data input, coding).

660.

660. The design and presentation of a web-based questionnaire to the respondent will differ from the paper version. Special care must be taken to minimize any potential mode effects arising from differences between the paper and electronic versions of the questionnaire, and between the different modes of compilation of electronic questionnaires (e.g. between CAWI i.e. self-enumeration and CAPI where an interview will be conducted). Hence, this should be an important topic to be considered in the testing programme for the questionnaire.

9.6.10 Measuring record linkage quality

9.6.10 Measuring record linkage quality

661.

661. One key aspect in the usage of administrative sources for censuses is the linkage process of various data sources. Often, determining the quality of a dataset will require its linkage to another dataset for comparison. Also, if the NSO relies on more than one source of administrative data for its census, it is necessary to be able to link data from the different sources at the unit/record level. The degree of success of such linkage will affect both the accuracy and the relevance of the input data.

662.

662. A common unique identifier reduces the effort required to link the data by making it easier to evaluate the completeness and accuracy of matching. In the absence of such an identifier, it is more difficult to link data reliably. In this case, record linkage using multiple variables that are common to the units in each data source (typically, name, date of birth, sex and address) may be possible. In this case, the NSO needs to be assured that such “matching” variables are of sufficient quality in all sources. Such a process may require deterministic and probabilistic record linkage strategies.

663.

663. This process may take place inside the NSO as part of the process stage, or outside the NSO, e.g. within the population register. In the case of record linkage taking place outside the NSO, a thorough documentation of the processes by the data-providing agency is crucial for quality assessment. Even though the existence and usage of universal identifiers should ensure the high quality of the record linkage performed by the third-party agency, the quality of it should be assessed in the source and data stage through the use of metadata and information provided by the data-providing agency. In addition, a cross-validation of the data provided is possible in the processing stage, if the data structure allows it. If record linkage is carried out inside the NSO as part of the census, the NSO has much more direct control over the process.

664.

664. The quality of record linkage can be assessed by statistical analysis, clerical reviews, or additional surveys. These allow for the calculation of quality measures such as false positives/negatives and recall value (see Quality measures for record linkage). However, regardless of the stage, a detailed and transparent measurement and reporting of record linkage processes’ quality is important in order to ensure the quality of the final product, a detailed and transparent documentation is vital to quality assessment and potential future improvements.

Quality measures for record linkage in the Germany register-based population census test

665.

665. In the case of the register-based population census test in Germany, a 12 percent sample of the German population was used to compare the results of the original 2022 census survey with that of a probabilistic record linkage model.

666.

666. In this process, the record linkage aims at matching the population register to records from ten administrative sources using a probabilistic record linkage strategy. The use of survey data from the 2022 census as external reference data allows for the calculation of quality measures for each administrative source and for the census database as a whole. The record linkage process is complemented by clerical reviews of potential matches and by statistical analysis, in order to optimize and validate the record linkage model.

667.

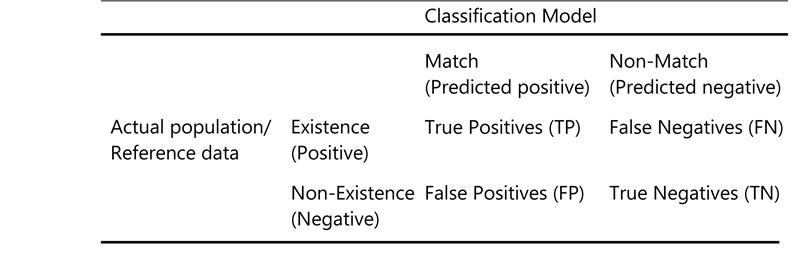

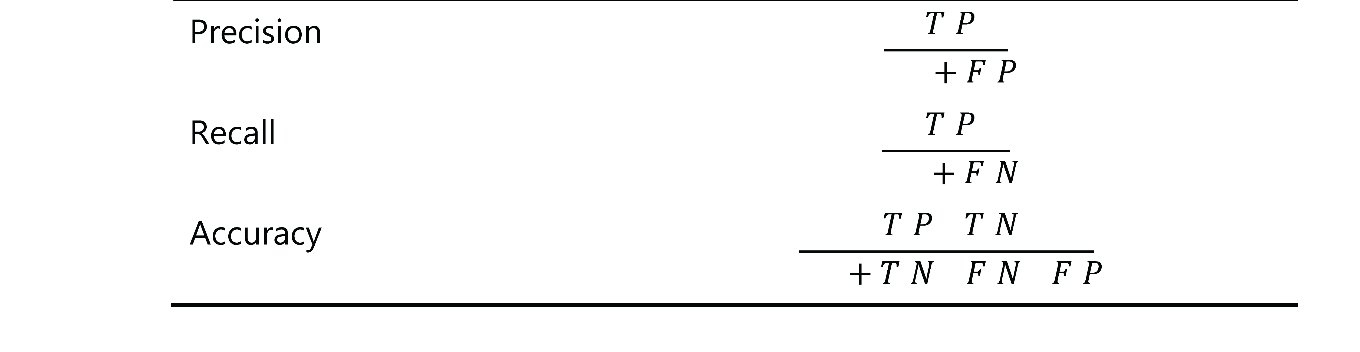

667. The confusion matrix (Table 1) is the baseline for the calculation of quality measures in record linkage using external reference data.

668.

668. The basic classification problem in record linkage is the match of records present in different sources and referred to the same person. In this perspective, the record linkage process aims at matching units already present into the census dataset (e.g. in the population register) with units in different administrative sources, and at associating them with the same code or id.

Table 1

Confusion matrix in record linkage

Confusion matrix in record linkage

669.

669. In a simplified form, a classification decision exists for every record representing a person in the census database regardless of whether a record matches another record in a different source or not. The reference data, e.g. a survey or another administrative source, serves as the external benchmark. Through the cross-tabulation between the variable indicating the existence of the unit in the reference data and the variable indicating the of the classification model, it is possible to categorize the data under four cases. From these four cases, the quality measures precision, recall and accuracy can be derived (Table 2).

Table 2

Quality measures for record linkage

Quality measures for record linkage

9.6.11 Measuring imputation quality in register-based censuses

9.6.11 Measuring imputation quality in register-based censuses

670.

670. The need for data editing and imputation does not decrease when administrative sources are used, as the existence of multiple data sources can be in itself a source of inconsistencies (when several register sources are used simultaneously to define, for each statistical unit, the value of the relevant variable, it becomes necessary to include rules for prioritization between different sources in the event of contradictory data). Under-coverage of data sources, data linkage problems and the use of sample data can lead to missing values that might require specific solutions. Improper imputation methods can lead to erroneous results. Therefore, an increasing need arises to assess the quality of data editing and imputation procedures.

671.

671. An important aspect of quality assurance for register-based censuses is imputation of missing values. This process is especially relevant for census variables that are taken from a non-integral source (i.e. a source that does not cover the entire population). In that case, mathematical methods are often used to make inferences for the population, by using deterministic and probabilistic imputation and weighting.

672.

672. For a sound interpretation of results, it is important to disseminate imputation rates for each cross-tabulation in the publication. Results for certain cross-tabulations that are insufficiently covered by any data source might not be published at all. For instance, Statistics Netherlands uses Labour Force Surveys as a source for the census variable Occupation. Any cell value that is covered by less than 25 observations is not published, due to a lack of confidence.

673.

673. If imputation or weighting is applied, the accuracy of these methods should be evaluated. Several methods are available. The distribution of a variable with and without imputations can be compared, comparisons can be made with other sources and mathematical methods can be applied. The latter includes: 1) analytical expressions for estimating confidence intervals, 2) resampling techniques like Bootstrapping and Jackknife and 3) cross-validation methods that apply estimation methods to observed records to assess estimation error.

674.

674. The assessment of imputation quality is not limited to the accuracy of individual imputations, but especially for a census it is also relevant to consider implications for all possible cross-tabulations, e.g. the number of 53 year-old, females with a certain educational level. In this respect, Chambers (2006) defines four criteria to evaluate imputation accuracy: 1) predictive accuracy 2) distributional accuracy; 3) estimation accuracy and 4) imputation plausibility.63

Box 1

Use of imputation for missing values in a register: the imputation of educational attainment in the Dutch register-based census

Use of imputation for missing values in a register: the imputation of educational attainment in the Dutch register-based census

In the Dutch register-based census, the variable “educational attainment” is derived from the so-called Educational Attainment File (EAF).

The coverage of this data sources is selective as the data cover approximately two thirds of the population; while younger persons are integrally observed, older persons are covered on a sample basis. All missing educational levels are estimated at micro level. This is done by a so-called multinomial logistic regression model, which takes the selectivity of data collection into account. The model has been exclusively designed for the census. This means that the imputed educational levels are not used for any other purpose.

A first step in the validation consists of a logical check of the estimated model. The estimated regression coefficients should not be extremely small or high, as this might point out to technical difficulties in estimating the model. Moreover, the estimated regression coefficient should conform to logical expectations, e.g. a positive correlation between income and educational level.

The final validation consists of a thorough comparison of the results with other educational statistics. Comparisons are not only made for the Dutch population as a whole, but also for detailed subpopulations, e.g. the distribution of the educational levels by geographic area, sex and age. Any significant deviations from other publications should be explainable.64

9.6.12 Managing coverage error

9.6.12 Managing coverage error

675.

675. Coverage is a critical element of accuracy. It has a direct influence on the quality of population counts and an indirect impact on the quality of all other data produced by the census. Thus, the coverage concerns should be taken into consideration in the design and implementation of most census activities. Enumeration area boundaries should be carefully defined and mapped to ensure that no area is omitted or included twice. Instructions and training on dwelling coverage for staff engaged in dwelling listing and enumeration should be clear, explicit and easy to understand. The target population must be well defined and related instructions and questions for both interviewers and respondents need to be carefully developed and thoroughly tested.

676.