Chapter 6 Developing a national well-being measurement framework

6.1 This chapter gives operational guidance to countries on developing a national well-being measurement framework. Section 6.1 provides a brief reminder of key issues to consider when establishing a national well-being framework. Section 6.2 outlines a step-by-step approach for developing a national framework to ensure a thorough process, engagement of users and stakeholders and a successful outcome and delivery. Section 6.3 provides guidance on engaging users and stakeholders to ensure buy-in, support and sustainability of the framework. Finally, Section 6.4 presents how New Zealand has developed a national well-being framework.

6.1 This chapter gives operational guidance to countries on developing a national well-being measurement framework. Section 6.1 provides a brief reminder of key issues to consider when establishing a national well-being framework. Section 6.2 outlines a step-by-step approach for developing a national framework to ensure a thorough process, engagement of users and stakeholders and a successful outcome and delivery. Section 6.3 provides guidance on engaging users and stakeholders to ensure buy-in, support and sustainability of the framework. Finally, Section 6.4 presents how New Zealand has developed a national well-being framework.

6.2 This section summarizes the approach to measuring well-being within a country context, based on the experiences of countries that have developed their own well-being frameworks.

6.2 This section summarizes the approach to measuring well-being within a country context, based on the experiences of countries that have developed their own well-being frameworks.

6.3 There are notable differences among national frameworks due to country specific conditions and user needs. The challenge of balancing international comparability with domestic user needs is common in many areas of statistical measurement, but may be particularly complex in this area due to the wide range of topics and data sources that may be used to assess a country's well-being. Despite differences, national frameworks share many components. Hence, when establishing a national framework, the following key issues should be considered:

6.3 There are notable differences among national frameworks due to country specific conditions and user needs. The challenge of balancing international comparability with domestic user needs is common in many areas of statistical measurement, but may be particularly complex in this area due to the wide range of topics and data sources that may be used to assess a country's well-being. Despite differences, national frameworks share many components. Hence, when establishing a national framework, the following key issues should be considered:

•

Selection of dimensions – how to balance and trade-off between economic, environmental or social dimensions of well-being.

•

Objective and subjective indicators – whether to include both types of indicators? For example, the level of household income in a country (objective) and households report on whether they are finding it difficult to get by financially (subjective).

•

Stock or flow measures – whether to include the levels of specific measures at a point in time or how they change over time, with or without an end goal? For certain measures, one may need to consider how to account for depletion, depreciation and degradation.

•

Unit of interest – the individual, the household, community, region or nation, or all? This is important both for the outcomes of interest (individual life satisfaction or community integration, for example) and if the data is to be disaggregated, for example, by communities or regions.

•

International comparison – the desire for international comparison can determine what is included in the framework.

•

Distributions – should the focus be on the headline metric or how that is distributed across the response scale, for example by geography, social class, income, sex or age?

•

Periodicity – how frequently will the indicators be updated, e.g., annually?

•

Human centricity – should humanity be at the heart of a well-being framework and its definition, or should it cover a wider canvas, including, e.g. nature and the environment, of which humanity is one part? Different societies or groups within society may perceive the answer to this question in different ways.

•

Culture – should the country's culture and norms be accounted for when defining well-being in a country or the framework’s population of interest? Or through the development of several frameworks to represent different sections of society? Or through indicators of engagement with historical and cultural sites or language?

•

Outcome versus drivers – whether to include outcome indicators only or also indicators of drivers of these outcomes? If only outcomes are presented, it is still essential to understand the drivers of these outcomes, and decision-makers may wish to consider the impact of their investment, policy and program levers.

•

Current and future well-being – although the national framework and these Guidelines may focus on current well-being, it is helpful to consider relations or overlaps with sustainability and future well-being, as these are important considerations in many people’s current well-being.

6.4 Chapter 3 highlights the recommended dimensions and indicators selected considering the above-listed issues. The Annex presents detailed information on each of the recommended indicators.

6.4 Chapter 3 highlights the recommended dimensions and indicators selected considering the above-listed issues. The Annex presents detailed information on each of the recommended indicators.

6.5 It is important to remember that culture is pervasive: each dimension of well-being ‘here and now’ exists in a particular cultural context. It is not merely something people do; it defines who people are and how they live.

6.5 It is important to remember that culture is pervasive: each dimension of well-being ‘here and now’ exists in a particular cultural context. It is not merely something people do; it defines who people are and how they live.

6.6 Cultural differences find their way into the language used to measure well-being. For example, Western cultures tend to be individualistic, defining well-being in terms of personal achievements, control and self-expression, whereas African culture is more collectivistic, emphasizing social connectedness and positive relations with others (Mullings et al. 2024). A recent OECD report (OECD 2024a) compared well-being initiatives in Bhutan, the Philippines, Thailand, Malaysia, Korea, and Japan with the OECD Well-being Framework. Bhutan, the Philippines, and Malaysia explicitly include culture as a dimension (including religion in the Philippines), while the interpretation of the dimension of social connections (in the OECD framework) appears to emphasize family and community rather than the individual. In Māori, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders cultures, spirituality and community are essential parts of well-being (Tse et al. 2005).15 In addition, many Indigenous populations are deeply connected to the nature and landscape in which they live (Sangha et al. 2018). Similar subjects are also considered important in Europe. For example, the Italian BES framework includes the theme ‘landscape and cultural heritage’ (paesaggio e patrimonio culturale).

6.6 Cultural differences find their way into the language used to measure well-being. For example, Western cultures tend to be individualistic, defining well-being in terms of personal achievements, control and self-expression, whereas African culture is more collectivistic, emphasizing social connectedness and positive relations with others (Mullings et al. 2024). A recent OECD report (OECD 2024a) compared well-being initiatives in Bhutan, the Philippines, Thailand, Malaysia, Korea, and Japan with the OECD Well-being Framework. Bhutan, the Philippines, and Malaysia explicitly include culture as a dimension (including religion in the Philippines), while the interpretation of the dimension of social connections (in the OECD framework) appears to emphasize family and community rather than the individual. In Māori, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders cultures, spirituality and community are essential parts of well-being (Tse et al. 2005).15 In addition, many Indigenous populations are deeply connected to the nature and landscape in which they live (Sangha et al. 2018). Similar subjects are also considered important in Europe. For example, the Italian BES framework includes the theme ‘landscape and cultural heritage’ (paesaggio e patrimonio culturale).

6.7 Having outlined the key considerations for the development of a national well-being framework, it is important to outline the steps for its practical development. Throughout, the United Kingdom will be used as an example for illustrative purposes.

6.7 Having outlined the key considerations for the development of a national well-being framework, it is important to outline the steps for its practical development. Throughout, the United Kingdom will be used as an example for illustrative purposes.

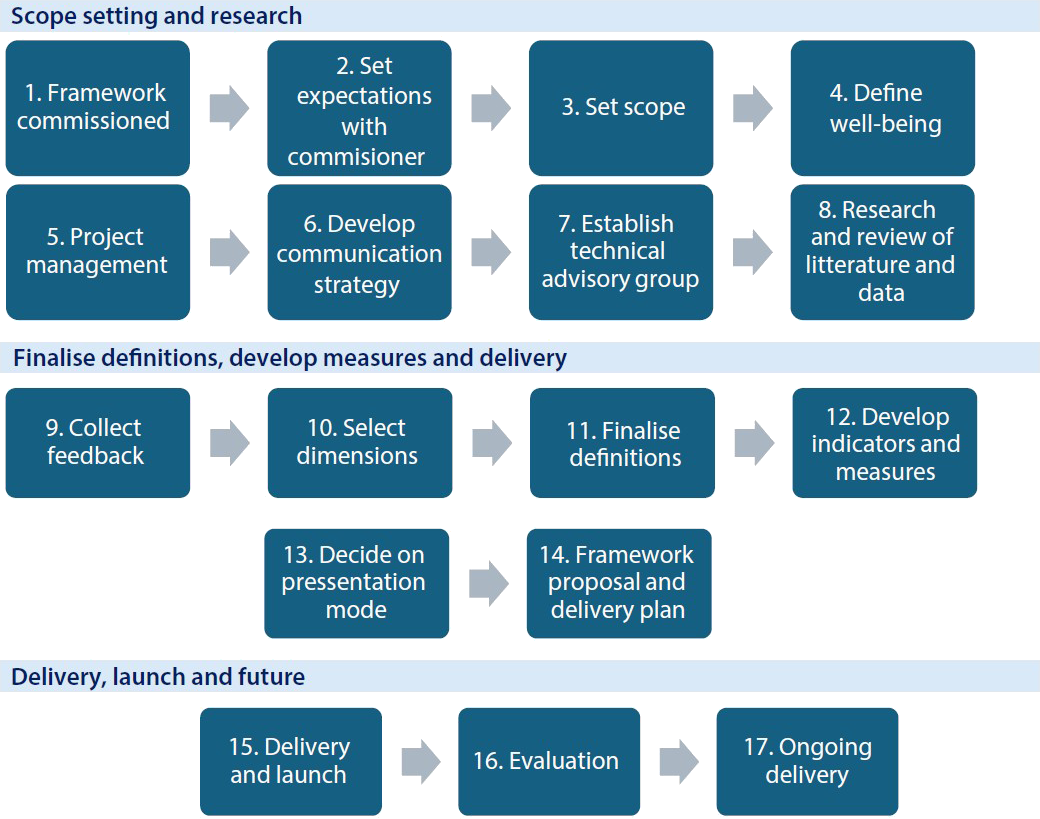

6.8 Figure 6.1 presents key steps in developing a national well-being framework. Details of the steps are provided in the following sections. While the flow chart suggests the steps are independent, in practice, many can progress in parallel. When developing a national framework, countries should adapt the steps to the national context and available resources.

6.8 Figure 6.1 presents key steps in developing a national well-being framework. Details of the steps are provided in the following sections. While the flow chart suggests the steps are independent, in practice, many can progress in parallel. When developing a national framework, countries should adapt the steps to the national context and available resources.

Figure 6.1

Steps in developing a national well-being framework

Steps in developing a national well-being framework

6.2.1 Scope setting and research

6.2.1 Scope setting and research  1. Framework commissioned

1. Framework commissioned

6.9 A well-being framework may be commissioned by a prime minister, minister or other. It is essential to understand the scope of the assignment from the beginning. This includes key factors such as the delivery timeline, available funds, the intended audience or coverage of the framework, and a rough idea of the expected end product. Knowing how negotiable these aspects are will influence several parameters throughout the project.

6.9 A well-being framework may be commissioned by a prime minister, minister or other. It is essential to understand the scope of the assignment from the beginning. This includes key factors such as the delivery timeline, available funds, the intended audience or coverage of the framework, and a rough idea of the expected end product. Knowing how negotiable these aspects are will influence several parameters throughout the project.

2. Set expectations with the commissioner

2. Set expectations with the commissioner

6.10 Discussions should centre on:

6.10 Discussions should centre on:

•

Number of indicators

-

Is the framework expected to include a smaller or larger set of indicators? Or should there be separate frameworks to provide comprehensive and summary indicator sets?

-

Is it planned to have a dashboard, a composite indicator, or a combination?

-

Understanding if the commissioner has a specific idea in mind from the beginning helps to shape the work programme accordingly

•

Purpose - who is the intended audience? Is the purpose of the framework to inform, to track change, to support decision makers throughout the policy cycle, or a combination of these?

•

Inclusion of children

-

Children are an important consideration for a well-being framework, both from the perspective of current and future well-being.

-

Ideally, the national framework should represent all in society, including children, but a decision can be made whether this is in the main framework or the establishment of a separate targeted framework. The UK has a separate framework for both children (0 to 15 year olds) and young people (16 to 24 year olds).

-

When making these decisions, one should bear in mind the availability of data for subsets of the population. For example, data on children is often relatively sparse (see Box 3.5).

•

Presentation: Is there a preference for a collection of indicators disseminated through a dashboard, composite indicators, or something else?

-

This understanding of preferences will help to set the scope of the literature review.

-

Having an idea of this from the beginning ensures that the right colleagues are consulted, for example, data visualisation colleagues for the establishment of a dashboard.

-

In the UK, from the inception in 2011, the well-being indicators have been presented as a suite. This format was initially presented as a static well-being wheel, but for digital inclusivity, it has since developed into an interactive dashboard.

3. Set scope

3. Set scope

6.11 It is essential to know the time and funding available to develop and maintain the framework, carry out research and build the communication tools to be able to work within realistic constraints.

6.11 It is essential to know the time and funding available to develop and maintain the framework, carry out research and build the communication tools to be able to work within realistic constraints.

6.12 Knowledge of funding in advance enables the commissioning of research projects, the development of new dissemination tools, and the organization of engagement events, including the potential launch of consultations, findings, or dissemination tools. If there is a short time frame, there may not be sufficient time to conduct research, which would necessitate relying on lessons learned from other countries. If there is more time, it is recommended to explore what well-being means in your specific country setting. This can be done through a national debate or qualitative research.

6.12 Knowledge of funding in advance enables the commissioning of research projects, the development of new dissemination tools, and the organization of engagement events, including the potential launch of consultations, findings, or dissemination tools. If there is a short time frame, there may not be sufficient time to conduct research, which would necessitate relying on lessons learned from other countries. If there is more time, it is recommended to explore what well-being means in your specific country setting. This can be done through a national debate or qualitative research.

6.13 In the UK, when establishing the framework, a national debate was held. This debate included face-to-face events, focus groups, and a survey, which cumulatively generated 34,000 responses. When reviewing their existing measures in 2022 and 2023, the UK undertook a consultation survey, which included asking respondents, via an open question, what they consider important to national well-being. They also added questions to one of their social surveys, gathering over 2,000 responses to the question “What is important to your own, and your community's well-being?”. Lastly, this was complemented with focus groups with selected groups who generally report low personal well-being in the UK. This approach was taken to balance funds and population coverage against timeliness.

6.13 In the UK, when establishing the framework, a national debate was held. This debate included face-to-face events, focus groups, and a survey, which cumulatively generated 34,000 responses. When reviewing their existing measures in 2022 and 2023, the UK undertook a consultation survey, which included asking respondents, via an open question, what they consider important to national well-being. They also added questions to one of their social surveys, gathering over 2,000 responses to the question “What is important to your own, and your community's well-being?”. Lastly, this was complemented with focus groups with selected groups who generally report low personal well-being in the UK. This approach was taken to balance funds and population coverage against timeliness.

4. Definition of well-being

4. Definition of well-being

6.14 It is key to clearly define what well-being means within the specific context of the country from the very beginning. Consider whether to use an existing definition as a foundation for the framework, or if not, identify the research needed to develop an appropriate definition. This clarity of definition will help in structuring the framework and determining the necessary measures for the required research. An example definition from the UK: ‘How we are doing as individuals, as a community and as a nation and how sustainable that is for the future.’

6.14 It is key to clearly define what well-being means within the specific context of the country from the very beginning. Consider whether to use an existing definition as a foundation for the framework, or if not, identify the research needed to develop an appropriate definition. This clarity of definition will help in structuring the framework and determining the necessary measures for the required research. An example definition from the UK: ‘How we are doing as individuals, as a community and as a nation and how sustainable that is for the future.’

6.15 When preparing the well-being definition, consider who/what is at the heart of the definition – is it humans, or is it the entire ecosystem where humans are only one part? Additionally, if it is humans, are all included? It might not be the case if the data sources only cover household populations or people aged over 15.

6.15 When preparing the well-being definition, consider who/what is at the heart of the definition – is it humans, or is it the entire ecosystem where humans are only one part? Additionally, if it is humans, are all included? It might not be the case if the data sources only cover household populations or people aged over 15.

6.16 There is no one way to look at well-being. People view well-being differently depending on their values, beliefs, and social norms. In New Zealand, Māori have a distinctive view of well-being. It is informed by te ao Māori (a Māori world view) where, for example, whenua (land) is not seen just for its economic potential, but through familial and spiritual connections defined by cultural concepts such as whakapapa (genealogy) and kaitiakitanga (stewardship).

6.16 There is no one way to look at well-being. People view well-being differently depending on their values, beliefs, and social norms. In New Zealand, Māori have a distinctive view of well-being. It is informed by te ao Māori (a Māori world view) where, for example, whenua (land) is not seen just for its economic potential, but through familial and spiritual connections defined by cultural concepts such as whakapapa (genealogy) and kaitiakitanga (stewardship).

6.17 When developing the definition of well-being and the framework as a whole, it is important to consider:

6.17 When developing the definition of well-being and the framework as a whole, it is important to consider:

•

Public opinion – the process of engaging with the public to understand what aspects of their lives they consider important to their well-being. This can be considered a lived experience approach.

•

User perceptions – the process of consulting users on the issues of most importance to them and which they wish to see included.

•

Expert opinion – the process of relying on expert insights to structure an offering to users.

6.18 Gathering public opinion helps to identify the nuances of the well-being, drivers and cultural components in the specific country setting and variation across population groups. By gathering user feedback, one can develop a tool that effectively meets their needs. Additionally, expert opinion allows building a conceptually robust framework and fit-for-purpose indicators, with a clear understanding of the drivers and interconnections between suggested measures.

6.18 Gathering public opinion helps to identify the nuances of the well-being, drivers and cultural components in the specific country setting and variation across population groups. By gathering user feedback, one can develop a tool that effectively meets their needs. Additionally, expert opinion allows building a conceptually robust framework and fit-for-purpose indicators, with a clear understanding of the drivers and interconnections between suggested measures.

5. Project Management

5. Project Management

6.19 Having gained information on key considerations and scope, it is helpful to establish project management by determining the responsible senior officer and drafting a chart with time and potential staff allocations. This can help determine the feasibility of the project’s goals based on the resources available.

6.19 Having gained information on key considerations and scope, it is helpful to establish project management by determining the responsible senior officer and drafting a chart with time and potential staff allocations. This can help determine the feasibility of the project’s goals based on the resources available.

6. Develop a communication strategy

6. Develop a communication strategy

6.20 It is essential to develop a communication strategy outlining which stakeholders to engage with, what information to share, and how and when to engage with them throughout the framework’s development, launch and beyond (see Chapter 5). The communication team should be involved in establishing this strategy.

6.20 It is essential to develop a communication strategy outlining which stakeholders to engage with, what information to share, and how and when to engage with them throughout the framework’s development, launch and beyond (see Chapter 5). The communication team should be involved in establishing this strategy.

6.21 Outline the stakeholders. The key stakeholders, based on the Strategic Communications Framework of Official Statistics (UNECE 2021), include:

6.21 Outline the stakeholders. The key stakeholders, based on the Strategic Communications Framework of Official Statistics (UNECE 2021), include:

•

Policy-makers

-

ministers, special advisors and senior civil servants (current or former)

-

mayors, local government cabinet members, political advisors, and senior officials

-

OECD, European Union and United Nations leaders and senior officials

-

International - it is helpful to learn from others’ experiences. At a national level, a country generally only sets up a national framework once, therefore it's essential to look internationally for guidance, lessons learnt and insights

•

Influencers

-

politicians

-

members of think-tanks and interest groups

-

academics (students and teachers)

-

commentators and senior journalists

-

business leaders

-

civil service leaders

-

leaders from non-profit organisations (the third sector). Note, it is especially important to engage with the third sector if it is not possible to carry out direct research with all sections of society, as they will provide advocacy and valuable insights

•

Scrutinisers

-

parliamentary committees and scrutiny committees

-

other national statistical leaders

-

international bodies (e.g., Eurostat, international statistical organisations)

-

statistical and digital bloggers, journalists, commentators, and social media influencers

-

academics (students and teachers)

-

information commissioners

-

privacy commissioners and campaigners

-

open data campaigners

•

Partners

-

funders

-

survey respondents

-

administrative data providers

-

syndicators and aggregators

-

academics and other innovators

•

General public

6.22 Plan engagement activities. There should be agreement about what the purpose of engaging with each stakeholder is. For example, promote the framework’s development, engage in research, promote the findings, raise awareness and use of the framework.

6.22 Plan engagement activities. There should be agreement about what the purpose of engaging with each stakeholder is. For example, promote the framework’s development, engage in research, promote the findings, raise awareness and use of the framework.

6.23 Outline available communication channels. Here, one can think outside of the norm by considering:

6.23 Outline available communication channels. Here, one can think outside of the norm by considering:

•

Social media – for example, tweets, LinkedIn posts, eBulletins. This is a good way to promote the development of the framework, publications or events, and generate engagement, including consultation activities. In the UK, many social media platforms were utilised to promote their consultation launch, associated surveys and research, as well as their findings and subsequent new tools. They also utilised relevant stakeholder e-newsletters across a breadth of well-being topic areas, including health and the labour market.

•

Formal consultation or national debate. For the NSO, there may be legal requirements on how to engage when developing new outputs. The UK carried out an informal consultation to gather feedback on the current framework and tool. Review of the Measures of National Well-being - Office for National Statistics - Citizen Space (ons.gov.uk)

•

Public engagement and speaking events, whether conducted online or in person, are vital for effective communication. For instance, organising launch events to introduce a consultation process or a final product is important, as is participating in existing events hosted by others to connect with a diverse array of stakeholders and subject matter experts. Well-being dashboards encompass various disciplines and subjects; therefore, it is crucial to gather input and aim to involve everyone in the process.

6.24 Timing should be evaluated from both a resource and a strategic perspective. This includes considering when to launch and complete the consultation, as well as when to publish and promote the findings. It is important to identify any relevant events or theme days that could align with these timelines for promotion, which may help maximize resources. In addition, for each of these collaboration or connection opportunities, think about who to engage with and what messages to communicate to them.

6.24 Timing should be evaluated from both a resource and a strategic perspective. This includes considering when to launch and complete the consultation, as well as when to publish and promote the findings. It is important to identify any relevant events or theme days that could align with these timelines for promotion, which may help maximize resources. In addition, for each of these collaboration or connection opportunities, think about who to engage with and what messages to communicate to them.

7. Establish a technical advisory group

7. Establish a technical advisory group

6.25 Given the breadth of topic areas and data sources necessary to compile a well-being framework, establishing a technical advisory group helps efficiently gather advice and feedback across many topic areas and organisations.

6.25 Given the breadth of topic areas and data sources necessary to compile a well-being framework, establishing a technical advisory group helps efficiently gather advice and feedback across many topic areas and organisations.

6.26 Below is a list of those to consider inviting to the technical advisory group. Within these groups, consideration should be given to include both policy-makers and data providers:

6.26 Below is a list of those to consider inviting to the technical advisory group. Within these groups, consideration should be given to include both policy-makers and data providers:

•

Government departmental colleagues

•

Topical experts in the NSO (e.g., national accounts, labour market, health)

•

Third-sector or charity experts

•

Academic experts

•

International experts

8. Research and review of literature and data

8. Research and review of literature and data

6.27 Once the outline for the scope, definition, and objectives of the well-being framework is established, research can be planned and executed. It is important to determine whether there is enough time to conduct primary research or if the focus will be on existing research.

6.27 Once the outline for the scope, definition, and objectives of the well-being framework is established, research can be planned and executed. It is important to determine whether there is enough time to conduct primary research or if the focus will be on existing research.

6.28 It is best practice to conduct research to understand what factors contribute to well-being within the specific context and culture of the country. This approach will help ensure that the framework is representative, recognize nuances among different population subsets, and fosters support and buy-in.

6.28 It is best practice to conduct research to understand what factors contribute to well-being within the specific context and culture of the country. This approach will help ensure that the framework is representative, recognize nuances among different population subsets, and fosters support and buy-in.

6.29 Here are examples from the UK, New Zealand and Canada of primary research that has been carried out previously:

6.29 Here are examples from the UK, New Zealand and Canada of primary research that has been carried out previously:

•

Adding questions to an existing survey - Individual and community well-being, Great Britain - Office for National Statistics (ons.gov.uk)

•

National debate – Indicators Aotearoa New Zealand – Ngā Tūtohu Aotearoa: Key findings from consultation and engagement (Stats NZ, 2019)

•

Focus groups and a new survey - Qualitative and Quantitative Research on a National Quality of Life Framework (Canada)

6.30 These Guidelines provide a sound foundation for developing a national framework, including common dimensions and recommended indicators. It is also recommended to explore national research and literature for adaptation to national context and needs, and to learn from peers in other countries when establishing a framework.

6.30 These Guidelines provide a sound foundation for developing a national framework, including common dimensions and recommended indicators. It is also recommended to explore national research and literature for adaptation to national context and needs, and to learn from peers in other countries when establishing a framework.

6.31 It is essential to understand what data is available. This will help in understanding whether:

6.31 It is essential to understand what data is available. This will help in understanding whether:

•

Is it necessary, and possible, to set up a new data collection?

•

The framework has gaps and presents an aspirational framework?

•

Is it possible to update data as frequently as the user requests, e.g., monthly or quarterly?

6.32 In addition, alongside evaluating how frequently each indicator is updated, this information will help in deciding how often to update the data in the framework. Will the updates be 'live,' occurring as new data becomes available, or is it better to opt for a quarterly update, based on data collected in the previous quarter and updating it at one time? It's important to note that a dashboard loses its usefulness as the data becomes outdated.

6.32 In addition, alongside evaluating how frequently each indicator is updated, this information will help in deciding how often to update the data in the framework. Will the updates be 'live,' occurring as new data becomes available, or is it better to opt for a quarterly update, based on data collected in the previous quarter and updating it at one time? It's important to note that a dashboard loses its usefulness as the data becomes outdated.

6.33 The development of a well-being framework may not necessarily imply that additional data collection must be made. In most cases, it is possible to populate a framework based on data that is already available in your country.

6.33 The development of a well-being framework may not necessarily imply that additional data collection must be made. In most cases, it is possible to populate a framework based on data that is already available in your country.

6.2.2 Finalise definitions, develop measures and delivery

6.2.2 Finalise definitions, develop measures and delivery  6.34 When the scope setting and research are done, there are two options:

6.34 When the scope setting and research are done, there are two options:

•

Build a new framework from scratch based on themes from your research, or

•

Use an existing framework, such as the OECD’s Better Life Index and use your research to adapt it.

6.35 In both cases, it is important to consider the common dimensions and indicators that are outlined in Chapter 3.

6.35 In both cases, it is important to consider the common dimensions and indicators that are outlined in Chapter 3.

9. Collect feedback

9. Collect feedback

6.36 Once the primary and secondary research is finalised, it is time to collect and summarise feedback and results that have emerged. It is useful to hold an internal workshop to review the evidence and establish the dimensions and indicators of the framework.

6.36 Once the primary and secondary research is finalised, it is time to collect and summarise feedback and results that have emerged. It is useful to hold an internal workshop to review the evidence and establish the dimensions and indicators of the framework.

6.37 There is often a demand for national and regional policy-relevant indicators that reference policy targets or legal norms and standards. NSOs may add additional indicators and, if helpful, subdimensions that are relevant to national policy goals or legal norms and standards. The inclusion criteria (section 3.3.1) can be used to select the right indicators. In general, timeliness will be a key criterion for policy-relevant statistical indicators.

6.37 There is often a demand for national and regional policy-relevant indicators that reference policy targets or legal norms and standards. NSOs may add additional indicators and, if helpful, subdimensions that are relevant to national policy goals or legal norms and standards. The inclusion criteria (section 3.3.1) can be used to select the right indicators. In general, timeliness will be a key criterion for policy-relevant statistical indicators.

6.38 Reference values can be country-specific, for example, where it concerns poverty thresholds or policy goals, or supranational (such as the goals of EU policy). Values may be laid down in law, such as environmental norms and standards. They may also be integral to national institutional arrangements. For example, differences between countries in participation in education may be caused by institutional differences in the structure of the educational system and the age of compulsory education.

6.38 Reference values can be country-specific, for example, where it concerns poverty thresholds or policy goals, or supranational (such as the goals of EU policy). Values may be laid down in law, such as environmental norms and standards. They may also be integral to national institutional arrangements. For example, differences between countries in participation in education may be caused by institutional differences in the structure of the educational system and the age of compulsory education.

10. Select dimensions

10. Select dimensions

6.39 Dimensions must be selected and defined. It is recommended to ensure a balance of dimensions and indicators across the three pillars of economy, environment and society, if there is no pre-defined structure. Examples of well-being frameworks include:

6.39 Dimensions must be selected and defined. It is recommended to ensure a balance of dimensions and indicators across the three pillars of economy, environment and society, if there is no pre-defined structure. Examples of well-being frameworks include:

•

Canada – Prosperity, Health, Society, Environment and Good Governance

•

UK – Personal well-being, Our relationships, Health, Where we live, What we do, Personal finance, Education and skills, Economy, Governance and Environment

•

OECD Better Life Index – Housing, Income, Jobs, Community, Education, Environment, Civic engagement, Health, Life Satisfaction, Safety and Work-Life Balance

6.40 The Guidelines in Chapter 3 outline common dimensions as: subjective well-being, material living conditions, work and leisure, housing, health, knowledge and skills, physical safety, social connections, civic engagement and environmental quality.

6.40 The Guidelines in Chapter 3 outline common dimensions as: subjective well-being, material living conditions, work and leisure, housing, health, knowledge and skills, physical safety, social connections, civic engagement and environmental quality.

11. Finalise definitions

11. Finalise definitions

6.41 If an established definition has been used, it is useful to evaluate its appropriateness and whether any adaptation is needed based on the research that was carried out. If a new definition were developed from scratch, it is useful to use the research to agree and finalise the definition based on what was outlined at the early stages of the project.

6.41 If an established definition has been used, it is useful to evaluate its appropriateness and whether any adaptation is needed based on the research that was carried out. If a new definition were developed from scratch, it is useful to use the research to agree and finalise the definition based on what was outlined at the early stages of the project.

12. Develop indicators and measures

12. Develop indicators and measures

6.42 To establish your proposed indicators and measures, you should set your inclusion criteria. As outlined in Chapter 3, the selection criteria should consider:

6.42 To establish your proposed indicators and measures, you should set your inclusion criteria. As outlined in Chapter 3, the selection criteria should consider:

•

Statistical qualities:

o

Timeliness and frequency

o

Credibility and comparability

•

Conceptual qualities

o

Validity

o

Relevance

o

Directional meaning (i.e., how should changes in indicators be interpreted in terms of their impact on well-being)

o

Universality

•

Practical considerations

o

Measurability

o

Disaggregation

o

Understandability

6.43 Select dimensions and indicators, and how they should be measured. Chapter 3 outlines these concepts as follows:

6.43 Select dimensions and indicators, and how they should be measured. Chapter 3 outlines these concepts as follows:

•

Dimensions selected to provide a comprehensive picture of the well-being framework.

•

Sub-dimensions may be used to break down dimensions in suitable subgroups. For instance, a dimension on work and leisure may be broken down into two subdimensions, work and leisure, respectively.

•

Indicators are statistical variables selected to provide a comprehensive picture of the dimensions of the framework.

•

Measure is how the indicator is presented. For example percentage of people who report their life satisfaction as low.

6.44 Throughout the process of deciding on indicators and measures, the following considerations should be kept in mind:

6.44 Throughout the process of deciding on indicators and measures, the following considerations should be kept in mind:

•

The scope of the well-being framework, and user needs and understanding.

•

Data availability. Are data available, or is there a need to set up a collection, including the ability to collect data over time?

•

Whether the measure covers the required level of geography and population groups.

•

Whether the framework will be presented in a dashboard, as a composite indicator or a combination, and how that impacts the number of measures and indicator definitions.

•

The balance of metrics presenting inequality across different population groups (for example, gender pay gap or Gini coefficient), and the possibility to disaggregate other metrics to present inequalities and distribution across society (for example, income by men and women, or life satisfaction by region).

•

Counts versus representation measures. For example, is it helpful to count the number of people with a reported disability or to ensure disaggregation of other measures by whether the respondent has a disability? The second of this would allow users to understand whether someone with a disability has a lower income than those who do not, experience more relative poverty and are more or less satisfied with their lives. It may also be helpful to consider combining the count data into a contextual indicator set.

•

The balance throughout the framework of subjective versus objective measures.

•

Whether to present only the headline measure or provide more in data tables? For example, if the measure is those reporting high life satisfaction, is it also necessary to report the number of those with low life satisfaction in the associated tables? In addition, consider whether to include the time series for everything or just the headline measure.

•

Will the measures be provided at the headline level only, or provide breakdowns by various characteristics such as age and sex? If so, how frequently should one update this information? Will this only be available in data tables, or can it be built into a data explorer or a dashboard?

6.45 Chapter 3 outlines common dimensions and recommended indicators that consider the above considerations. NSOs may wish to adapt dimensions and indicators to better reflect country-specific perspectives on well-being while retaining international comparability and the comprehensive nature of the framework. Specific indicators and subdimensions can be added to provide a place for the associated indicators. It is advisable to ensure that the indicator set has an overlap with the recommended indicators in section 3.3. Thus, measurement will remain internationally comparable, while supporting a narrative that is specific to the country, culture, region or population group whose well-being is measured. Adaptation should not be done for reasons (political or otherwise) that violate the conceptual integrity and consistency of statistical measurement.

6.45 Chapter 3 outlines common dimensions and recommended indicators that consider the above considerations. NSOs may wish to adapt dimensions and indicators to better reflect country-specific perspectives on well-being while retaining international comparability and the comprehensive nature of the framework. Specific indicators and subdimensions can be added to provide a place for the associated indicators. It is advisable to ensure that the indicator set has an overlap with the recommended indicators in section 3.3. Thus, measurement will remain internationally comparable, while supporting a narrative that is specific to the country, culture, region or population group whose well-being is measured. Adaptation should not be done for reasons (political or otherwise) that violate the conceptual integrity and consistency of statistical measurement.

13. Decide on presentation mode

13. Decide on presentation mode

6.46 Once the indicators have been established, the next step is to decide how to present these measures. Options include:

6.46 Once the indicators have been established, the next step is to decide how to present these measures. Options include:

•

Visuals, for example, static or interactive charts

•

Dashboards

•

Written summaries

•

Explorer tools

6.47 When making this decision, it is important to remember that data presentation must be practically usable and needs to be clear and accessible to users without oversimplification.

6.47 When making this decision, it is important to remember that data presentation must be practically usable and needs to be clear and accessible to users without oversimplification.

14. Framework proposal and delivery plan

14. Framework proposal and delivery plan

6.48 Once research has been completed and reviewed, a framework proposal and delivery plan should be drafted. The proposal should include:

6.48 Once research has been completed and reviewed, a framework proposal and delivery plan should be drafted. The proposal should include:

•

definition of well-being

•

agreed output, for example, a dashboard or a composite indicator

•

framework/s structure

•

proposed indicators

•

dissemination approach

•

promotion and launch plans

6.49 When drafting the delivery plan, it is important to be realistic. For example, if it is agreed to publish updates quarterly, every six months, or annually, one should specify whether the initial focus will be on headline metrics for each measure, with plans to incorporate disaggregation and distributional analysis in future iterations. This iterative approach can enhance the sustainability and longevity of the research program by avoiding inflated budgets and adapting to changing user needs at each stage.

6.49 When drafting the delivery plan, it is important to be realistic. For example, if it is agreed to publish updates quarterly, every six months, or annually, one should specify whether the initial focus will be on headline metrics for each measure, with plans to incorporate disaggregation and distributional analysis in future iterations. This iterative approach can enhance the sustainability and longevity of the research program by avoiding inflated budgets and adapting to changing user needs at each stage.

6.50 Once the framework proposal and delivery plan are established, it is important to review them with stakeholders. Examples of stakeholders to review the proposal include:

6.50 Once the framework proposal and delivery plan are established, it is important to review them with stakeholders. Examples of stakeholders to review the proposal include:

•

Expert advisory panel/ technical advisory group

•

Senior leaders, including directors. This should also include directors of other relevant topic areas.

•

Depending on who the commissioner is, it may be pertinent to brief the Minister or their office to get first comments

•

Communications and data visualisation colleagues

•

Relevant data owners

•

Production team

6.51 After collecting and considering all feedback on the first iteration, incorporate the comments and adjust the well-being framework as necessary.

6.51 After collecting and considering all feedback on the first iteration, incorporate the comments and adjust the well-being framework as necessary.

6.52 Having finalised the proposal, follow the organisation’s sign-off procedure.

6.52 Having finalised the proposal, follow the organisation’s sign-off procedure.

6.2.3 Delivery, launch and future

6.2.3 Delivery, launch and future  15. Delivery and launch

15. Delivery and launch

6.53 The delivery and launch process can vary from organisation to organisation. Usually, it will involve the following steps:

6.53 The delivery and launch process can vary from organisation to organisation. Usually, it will involve the following steps:

•

Design, access and analyse

-

Design questions and surveys as needed or gain access to required administrative data.

-

Request published data, at the required granularity, as needed.

-

Request access to micro data, as needed.

-

Analyse to your specifications.

•

Visualise - work with the data visualisation colleagues to provide them with the data needed to populate the agreed visualisations.

•

Publish - follow your organisation’s procedures in publishing the framework and associated outputs. It may be useful to include references to international frameworks and guidelines that have been used in developing the national framework.

•

Promote - outline how to promote the development and publication of the framework. This promotion may be through written publications or online, or in-person events, and may include targeted communication to stakeholders and user groups.

16. Evaluation

16. Evaluation

6.54 Evaluation should be carried out and considered throughout the framework’s development. As noted in the United Kingdom’s Magenta book on Evaluation, the evaluation could consider each element of the framework's development and publication, including the process that was followed, the impact it had and its value for money.

6.54 Evaluation should be carried out and considered throughout the framework’s development. As noted in the United Kingdom’s Magenta book on Evaluation, the evaluation could consider each element of the framework's development and publication, including the process that was followed, the impact it had and its value for money.

6.55 Alongside the formalised evaluation guidance, it can be useful to carry out a reflection exercise after initial delivery. This helps the researchers involved in its development to outline lessons learnt through the process.

6.55 Alongside the formalised evaluation guidance, it can be useful to carry out a reflection exercise after initial delivery. This helps the researchers involved in its development to outline lessons learnt through the process.

6.56 It is also useful to carry out an additional exercise a year (or more) after launch to explore whether the framework is delivering what was originally outlined and whether there is a need to adapt to user demands. Examples of things to explore include:

6.56 It is also useful to carry out an additional exercise a year (or more) after launch to explore whether the framework is delivering what was originally outlined and whether there is a need to adapt to user demands. Examples of things to explore include:

•

If there were no plans for an aspirational framework, was it possible to have data for every measure?

•

Can the terminology used be improved based on the received feedback? In the UK, for example, feedback was received within the first year on the terms used for the labelling of changes over time in the dashboard. As a result, terms were changed from ‘Improvement’ and ‘Decline’ to ‘Positive change’ and ‘Negative change’.

17. Ongoing delivery

17. Ongoing delivery

6.57 Once the framework is established, it is important to work through the delivery plan. The framework’s credibility should be established at its launch. However, the framework should not be considered a fixed entity. Key to the framework’s success will be the ability to adapt to changing user needs. However, changes should be made in a transparent way and following agreed-upon criteria. Continuous changes of the framework may harm its credibility and adversely affect policy makers ability to select appropriate measures to monitor long-term outcomes.

6.57 Once the framework is established, it is important to work through the delivery plan. The framework’s credibility should be established at its launch. However, the framework should not be considered a fixed entity. Key to the framework’s success will be the ability to adapt to changing user needs. However, changes should be made in a transparent way and following agreed-upon criteria. Continuous changes of the framework may harm its credibility and adversely affect policy makers ability to select appropriate measures to monitor long-term outcomes.

6.58 It is also important to refresh the communication strategy to agree on how to continually gain stakeholder feedback and promote the framework on an ongoing basis.

6.58 It is also important to refresh the communication strategy to agree on how to continually gain stakeholder feedback and promote the framework on an ongoing basis.

6.59 Having outlined the conceptual considerations and common steps for establishing a national well-being framework, this section provides recommendations to support progress. The discussion in Chapter 6 so far has mostly covered technical aspects of building an indicator set for measuring national well-being. However, no matter how technically robust such an indicator set will be, it is vital also to build consensus during its development for it to have a practical impact. In most countries, even where national well-being frameworks are well-established, it is much more common for public and policy debate to be driven by key economic indicators such as GDP, inflation and unemployment than by broader well-being indicators. If the long-term goal is to change this situation and promote ‘well-being’ as the overarching goal, then this requires changing people’s perspectives as well as technical excellence.

6.59 Having outlined the conceptual considerations and common steps for establishing a national well-being framework, this section provides recommendations to support progress. The discussion in Chapter 6 so far has mostly covered technical aspects of building an indicator set for measuring national well-being. However, no matter how technically robust such an indicator set will be, it is vital also to build consensus during its development for it to have a practical impact. In most countries, even where national well-being frameworks are well-established, it is much more common for public and policy debate to be driven by key economic indicators such as GDP, inflation and unemployment than by broader well-being indicators. If the long-term goal is to change this situation and promote ‘well-being’ as the overarching goal, then this requires changing people’s perspectives as well as technical excellence.

6.60 The process of building national consensus requires attention to the views, needs and preferences of several key stakeholder groups:

6.60 The process of building national consensus requires attention to the views, needs and preferences of several key stakeholder groups:

•

The general public at large

•

The media

•

Policymakers and politicians at national, regional and local levels

•

Civil society organizations

•

Researchers and academic institutions

6.61 The successful establishment of a national well-being framework should involve all of these groups and provide sufficient time for different views to be aired and considered. It is important that this process is transparent and that it is seen to make a difference to the final shape and content of the indicator set. Chapter 5 provides more details on reaching out to user groups.

6.61 The successful establishment of a national well-being framework should involve all of these groups and provide sufficient time for different views to be aired and considered. It is important that this process is transparent and that it is seen to make a difference to the final shape and content of the indicator set. Chapter 5 provides more details on reaching out to user groups.

6.3.1 Who to involve in the process

6.3.1 Who to involve in the process  6.62 Establishing and maintaining a well-being framework is, at its core, also a stakeholder engagement exercise. Some of these stakeholders are obvious, while others may not be.

6.62 Establishing and maintaining a well-being framework is, at its core, also a stakeholder engagement exercise. Some of these stakeholders are obvious, while others may not be.

6.63 Policy teams and Ministers should be included to ensure that the framework meets their needs; it should be easy to understand and use.

6.63 Policy teams and Ministers should be included to ensure that the framework meets their needs; it should be easy to understand and use.

6.64 Organisational directors and leaders. Being multi-dimensional, it is important to bring additional directors and leaders from your organisation as they have the authority to help along the way, with access to data or meeting the framework needs with surveys. An example of engagement may include a periodic update email during the establishment of the framework to share how it is progressing.

6.64 Organisational directors and leaders. Being multi-dimensional, it is important to bring additional directors and leaders from your organisation as they have the authority to help along the way, with access to data or meeting the framework needs with surveys. An example of engagement may include a periodic update email during the establishment of the framework to share how it is progressing.

6.65 Data providers and survey teams - it is essential to have data in place to monitor the measures effectively. Populating the framework may require additional data collection or an increase in the frequency of existing data. These colleagues can assist in understanding what data is already being collected and what is feasible to obtain within specific timeframes.

6.65 Data providers and survey teams - it is essential to have data in place to monitor the measures effectively. Populating the framework may require additional data collection or an increase in the frequency of existing data. These colleagues can assist in understanding what data is already being collected and what is feasible to obtain within specific timeframes.

6.66 Community groups and NGOs - When developing a national framework, it is crucial to ensure that it represents everyone in society. Collecting representative voices from minority groups can be challenging, so it is essential to seek support and collaboration from organizations that represent these groups. This approach helps ensure that their perspectives are adequately considered.

6.66 Community groups and NGOs - When developing a national framework, it is crucial to ensure that it represents everyone in society. Collecting representative voices from minority groups can be challenging, so it is essential to seek support and collaboration from organizations that represent these groups. This approach helps ensure that their perspectives are adequately considered.

6.67 Analysts in departments and cross-departmental sharing forums. Analysts in departments not only need to provide the data their department holds for certain measures, but it is also important to get their buy-in on your approach to measuring well-being so they are your departmental advocates.

6.67 Analysts in departments and cross-departmental sharing forums. Analysts in departments not only need to provide the data their department holds for certain measures, but it is also important to get their buy-in on your approach to measuring well-being so they are your departmental advocates.

6.68 Advisory groups - It is essential to share the research with established advisory groups in the topic area and to form a new advisory group comprising both public and non-public sector organizations to provide guidance throughout the process.

6.68 Advisory groups - It is essential to share the research with established advisory groups in the topic area and to form a new advisory group comprising both public and non-public sector organizations to provide guidance throughout the process.

6.69 Data visualization. Regardless of the end goal, be it a suite of measures, a dashboard or a composite indicator, it’s important to bring the data visualisation team in early. When consulting users on what measures they want included, also ask how they want it disseminated and how often. The data visualisation colleagues will be able to support in outlining the information needed to know how to best develop a tool for dissemination, be that static images and graphics, branding or interactive explorer tools.

6.69 Data visualization. Regardless of the end goal, be it a suite of measures, a dashboard or a composite indicator, it’s important to bring the data visualisation team in early. When consulting users on what measures they want included, also ask how they want it disseminated and how often. The data visualisation colleagues will be able to support in outlining the information needed to know how to best develop a tool for dissemination, be that static images and graphics, branding or interactive explorer tools.

6.70 Communications team is essential to support reaching out to external organisations, utilising established mailing lists and channels of communication. For example, promoting the new framework on social media or encouraging participation in an online consultation. Often communications team have established routine catch-ups and advisory boards. These can be utilized to share information, gain buy-in and get input. It can assist in drafting a communication strategy that aligns with the needs of the framework once the scope and scale of engagements are determined.

6.70 Communications team is essential to support reaching out to external organisations, utilising established mailing lists and channels of communication. For example, promoting the new framework on social media or encouraging participation in an online consultation. Often communications team have established routine catch-ups and advisory boards. These can be utilized to share information, gain buy-in and get input. It can assist in drafting a communication strategy that aligns with the needs of the framework once the scope and scale of engagements are determined.

6.71 Media team (if separate from the communications team). The media team will be able to advise both in publicising the product specifically to the media once it is developed, and also through the development process to make sure it is easy to understand and disseminate. The media team is great at translating the research for the general public, which is an important stakeholder for well-being frameworks.

6.71 Media team (if separate from the communications team). The media team will be able to advise both in publicising the product specifically to the media once it is developed, and also through the development process to make sure it is easy to understand and disseminate. The media team is great at translating the research for the general public, which is an important stakeholder for well-being frameworks.

6.72 Sceptics – It is important to recognize that there may be critics of the well-being framework. Engaging with these sceptics is essential, as their feedback can help identify issues that need to be addressed. By listening to their concerns and considering their perspectives, there is an opportunity to convert them into advocates for the research and the product.

6.72 Sceptics – It is important to recognize that there may be critics of the well-being framework. Engaging with these sceptics is essential, as their feedback can help identify issues that need to be addressed. By listening to their concerns and considering their perspectives, there is an opportunity to convert them into advocates for the research and the product.

6.3.2 Long-term maintenance

6.3.2 Long-term maintenance  6.73 Building a national indicator set cannot be viewed as a one-off process that produces a fixed outcome. It is vital to establish an indicator set which is durable and to which there is a long-term commitment. On the other hand, it will be necessary for this indicator set to evolve over time. One reason is that new issues may emerge as important, for an example, in relation to digital well-being, civic engagement or environmental conditions. In such cases, the NSO may consider including new indicators.

6.73 Building a national indicator set cannot be viewed as a one-off process that produces a fixed outcome. It is vital to establish an indicator set which is durable and to which there is a long-term commitment. On the other hand, it will be necessary for this indicator set to evolve over time. One reason is that new issues may emerge as important, for an example, in relation to digital well-being, civic engagement or environmental conditions. In such cases, the NSO may consider including new indicators.

6.74 A second reason is data availability. Relying only on available data may introduce significant gaps and distortions to the overall picture. This carries substantial risks which may lead to sub-optimal or even negative impacts on the population and to the perpetuation of existing problems. For example, some countries may underinvest in mental health services compared to physical health services. Often, this goes hand in hand with much stronger data availability on the physical health of the population than on the mental health. If this imbalance is reflected in the national indicator set, it is possible that the attention of policymakers, the media and the public will be disproportionately focused on trends in physical health indicators, which may exacerbate the lack of attention to, and investment in, mental health services.

6.74 A second reason is data availability. Relying only on available data may introduce significant gaps and distortions to the overall picture. This carries substantial risks which may lead to sub-optimal or even negative impacts on the population and to the perpetuation of existing problems. For example, some countries may underinvest in mental health services compared to physical health services. Often, this goes hand in hand with much stronger data availability on the physical health of the population than on the mental health. If this imbalance is reflected in the national indicator set, it is possible that the attention of policymakers, the media and the public will be disproportionately focused on trends in physical health indicators, which may exacerbate the lack of attention to, and investment in, mental health services.

6.75 Another important aspect of over-reliance on what already exists is that such data may miss the issues faced by some sections of the population. Lack of data that can be disaggregated will prevent a full assessment of well-being and the identification of groups for which particular attention is needed to reduce inequalities. Attention needs to be paid to minority groups that may also be disadvantaged. It is important to ensure that data represents the well-being of these groups, and this may be achieved through booster samples and/or tailored additional data collection, such as survey work.

6.75 Another important aspect of over-reliance on what already exists is that such data may miss the issues faced by some sections of the population. Lack of data that can be disaggregated will prevent a full assessment of well-being and the identification of groups for which particular attention is needed to reduce inequalities. Attention needs to be paid to minority groups that may also be disadvantaged. It is important to ensure that data represents the well-being of these groups, and this may be achieved through booster samples and/or tailored additional data collection, such as survey work.

6.76 In addition, data may exclude particular groups, one example being the exclusion of specific age groups of the population. Many data that is gathered at the individual level has lower age limits, often 18 years old or 15 years old, and so excludes all or most children. Often, the only rationale for this is historical practice. For example, children from a certain age are quite capable of expressing how safe they feel, and this is equally valid as when an adult does so. There may also be exclusions related to elderly people – for example, some surveys are only of the working-age population.

6.76 In addition, data may exclude particular groups, one example being the exclusion of specific age groups of the population. Many data that is gathered at the individual level has lower age limits, often 18 years old or 15 years old, and so excludes all or most children. Often, the only rationale for this is historical practice. For example, children from a certain age are quite capable of expressing how safe they feel, and this is equally valid as when an adult does so. There may also be exclusions related to elderly people – for example, some surveys are only of the working-age population.

6.77 To ensure and maintain the national well-being measurement framework over time, it is helpful to include the following issues in the long-term planning:

6.77 To ensure and maintain the national well-being measurement framework over time, it is helpful to include the following issues in the long-term planning:

Maintain flexibility to adapt to changes

Maintain flexibility to adapt to changes

6.78 Being able to adapt is essential. Adaptation may be the addition or removal of indicators, provision of extra breakdowns of statistics or creation of a new explorer tool. Changes may be at the request of a policymaker or due to changes in definitions or data sources. If removing or adding indicators to the framework, make sure this is done based on established criteria, so this process is transparent to users. In the UK Measures of National Well-being, changes to measures are outlined each quarter in their data tables. They highlight both the change and the reason for the change.

6.78 Being able to adapt is essential. Adaptation may be the addition or removal of indicators, provision of extra breakdowns of statistics or creation of a new explorer tool. Changes may be at the request of a policymaker or due to changes in definitions or data sources. If removing or adding indicators to the framework, make sure this is done based on established criteria, so this process is transparent to users. In the UK Measures of National Well-being, changes to measures are outlined each quarter in their data tables. They highlight both the change and the reason for the change.

Clear allocation of responsibilities

Clear allocation of responsibilities

6.79 After the framework has been established, it is helpful to ensure a clear allocation of responsibilities and tasks to ensure it is maintained, updated and published according to plan.

6.79 After the framework has been established, it is helpful to ensure a clear allocation of responsibilities and tasks to ensure it is maintained, updated and published according to plan.

Shared ownership

Shared ownership

6.80 It is helpful to create a sense of shared ownership, as with multiple topics, gaps can easily happen. With measures across multiple sources, it is important to maintain effective engagement across all source owners and instil in them a shared ownership of the framework. Show them what they are contributing to and what impact it is having.

6.80 It is helpful to create a sense of shared ownership, as with multiple topics, gaps can easily happen. With measures across multiple sources, it is important to maintain effective engagement across all source owners and instil in them a shared ownership of the framework. Show them what they are contributing to and what impact it is having.

6.81 If an expert advisory panel for the establishment of the framework is set up, consider keeping it with less frequent meetings or with purely email updates. It is beneficial to continue to have their input and advice. This group will be able to act as advocates for the framework across departments and sectors.

6.81 If an expert advisory panel for the establishment of the framework is set up, consider keeping it with less frequent meetings or with purely email updates. It is beneficial to continue to have their input and advice. This group will be able to act as advocates for the framework across departments and sectors.

Maintain comparability over time

Maintain comparability over time

6.82 Changes over time are an important element of well-being frameworks. To ensure changes are captured, indicators should be monitored and kept comparable over time.

6.82 Changes over time are an important element of well-being frameworks. To ensure changes are captured, indicators should be monitored and kept comparable over time.

Communication

Communication

6.83 Timely media presence will help to ensure the framework’s existence is maintained in people’s minds. It is advised to work with the media/communication teams to promote the framework and its findings at each data update. Things to consider include:

6.83 Timely media presence will help to ensure the framework’s existence is maintained in people’s minds. It is advised to work with the media/communication teams to promote the framework and its findings at each data update. Things to consider include:

•

Language needs to be clear, understandable and accessible.

•

The well-being framework and its underlying dimensions must be clearly defined and understood by stakeholders and users.

•

Consistent language and terms throughout are essential. Language consistency supports users’ understanding and their ability to advocate the framework to others.

•

Consider the needs of target audiences and tailor the statistical products to optimise the communications.

6.84 Section 6.2 provides an overview of key steps to consider when developing a framework for measuring well-being. However, practices will vary. Some countries may merge or skip steps, e.g., if procedures are already in place, or the sequence of the steps may differ. Differences in data availability and the intended use of the framework will also have an impact on how the framework is developed. Below is an example from New Zealand of how complementary well-being frameworks have been established and are used in decision making.

6.84 Section 6.2 provides an overview of key steps to consider when developing a framework for measuring well-being. However, practices will vary. Some countries may merge or skip steps, e.g., if procedures are already in place, or the sequence of the steps may differ. Differences in data availability and the intended use of the framework will also have an impact on how the framework is developed. Below is an example from New Zealand of how complementary well-being frameworks have been established and are used in decision making.

6.4.1 Background of well-being in New Zealand

6.4.1 Background of well-being in New Zealand  6.85 Successive Aotearoa New Zealand Governments have applied elements of well-being approaches (New Zealand Productivity Commission, 2023).

6.85 Successive Aotearoa New Zealand Governments have applied elements of well-being approaches (New Zealand Productivity Commission, 2023).

6.86 The 1999 to 2009 Government introduced ‘whole of government’ goals and outcomes, as part of its Reducing Inequalities policy, and the 2017 to 2023 Government embedded well-being into the Public Finance Act. This Act now requires governments to set well-being objectives to frame each Budget and requires the Treasury to prepare an independent report on well-being in New Zealand every four years. The government introduced its first Well-being Budget in 2019, where agencies were expected to identify the impacts of proposed budget initiatives using well-being frameworks.

6.86 The 1999 to 2009 Government introduced ‘whole of government’ goals and outcomes, as part of its Reducing Inequalities policy, and the 2017 to 2023 Government embedded well-being into the Public Finance Act. This Act now requires governments to set well-being objectives to frame each Budget and requires the Treasury to prepare an independent report on well-being in New Zealand every four years. The government introduced its first Well-being Budget in 2019, where agencies were expected to identify the impacts of proposed budget initiatives using well-being frameworks.

6.87 Against this background, the Treasury has been iteratively developing its Living Standards Framework (LSF) since 2011 and released the LSF Dashboard in 2018 to support strategic policy advice. Stats NZ - Tatauranga Aotearoa (New Zealand’s National Statistics Office) produced Ngā Tūtohu Aotearoa in 2019 to support the monitoring of well-being more generally. There was extensive collaboration between the Treasury and Stats NZ in the design of these complementary products.

6.87 Against this background, the Treasury has been iteratively developing its Living Standards Framework (LSF) since 2011 and released the LSF Dashboard in 2018 to support strategic policy advice. Stats NZ - Tatauranga Aotearoa (New Zealand’s National Statistics Office) produced Ngā Tūtohu Aotearoa in 2019 to support the monitoring of well-being more generally. There was extensive collaboration between the Treasury and Stats NZ in the design of these complementary products.

6.88 Ngā Tūtohu Aotearoa is a national indicator framework for well-being that can be used as a base in developing customised well-being monitoring frameworks. It shows a wide range of well-being outcomes and, where possible, how they vary over time, between population groups, and across New Zealand. Establishing a comprehensive suite of indicators that show how New Zealand is progressing was needed for several reasons:

6.88 Ngā Tūtohu Aotearoa is a national indicator framework for well-being that can be used as a base in developing customised well-being monitoring frameworks. It shows a wide range of well-being outcomes and, where possible, how they vary over time, between population groups, and across New Zealand. Establishing a comprehensive suite of indicators that show how New Zealand is progressing was needed for several reasons:

•

To improve decision-making by providing a wider view of progress.

•

To enable government investment to be more effectively directed towards improving the overall well-being of New Zealanders, alongside economic growth.

•